The Political Causes of the College Enrollment Crisis

Republican high schoolers don’t want to attend college anymore. That’s a problem for conservatives, for colleges, and for the country.

College enrollment is in “crisis.” According to the National Center for Education Statistics, “Between fall 2010 and fall 2021, total undergraduate enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions decreased by 15 percent (from 18.1 million to 15.4 million students).” After a small spike in 2022, freshman enrollment declined again in 2023, with “the plunge in enrollment the worst ever recorded.”

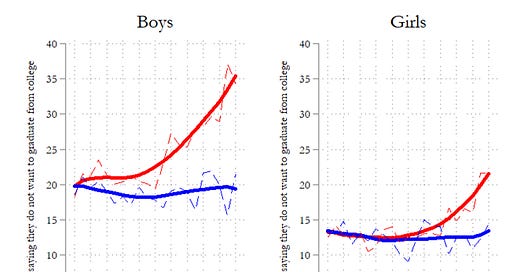

Low birth rates are part of the story behind this “enrollment cliff.” But, they are only part. Just as important is the growing disinterest that many high school students have in graduating from college. According to data from Monitoring the Future, a long-running survey of American 12th graders, the percentage of high school seniors reporting no interest in graduating from a four-year college rose from 18% to 28% between 2011 and 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Increasing Disinterest in College

So why are high school students suddenly disinterested in college? The most commonly cited culprits are non-college career opportunities, costs and COVID. Yet, these explanations ignore two critical facts about growing disinterest in pursuing higher education: nearly all of the increase has happened since 2010 and nearly all of the increase has happened among Republican high school students.

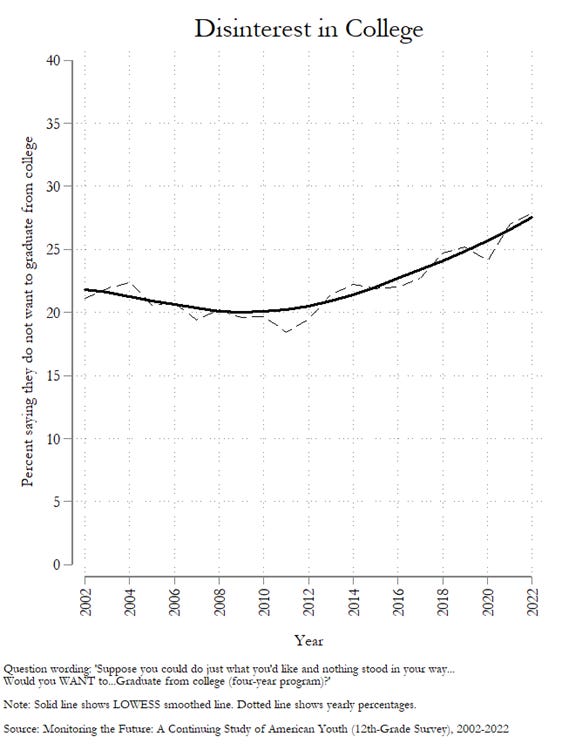

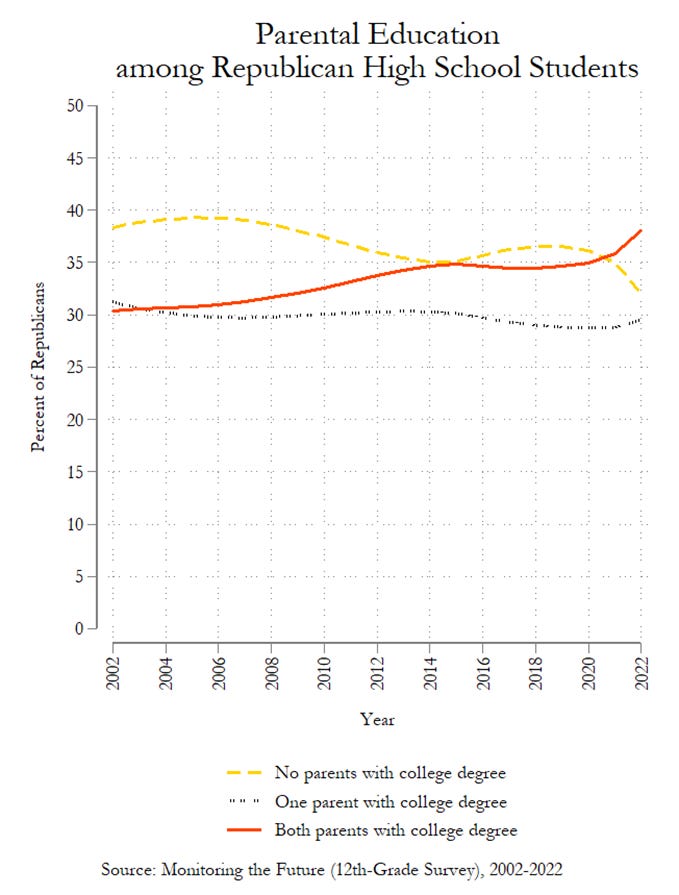

The figure below shows results from Monitoring the Future’s survey question on college disinterest between 2002 and 2022 (the most recently released data) disaggregated by gender and partisanship. While Democratic boys and girls have expressed roughly the same desire to graduate from college since 2002, Republican high school students have significantly less interest in higher education than they did twenty years ago. What’s more, the disaffection of conservative high schoolers is a relatively recent occurrence, with the percentage of Republican boys uninterested in college increasing 16% and the percentage of Republican girls uninterested in college increasing 9% since 2010 (Figure 2). Disinterest among Independents (not shown) is also up among boys (20% to 26%) and girls (14% to 18%) since 2010.

Figure 2 – Increasing Disinterest by Gender and Ideology

Economics and pandemics alone cannot explain the timing or ideological asymmetry of these preferences. The central question, then, is why have Republican high school students become so disinterested in higher education since 2010?

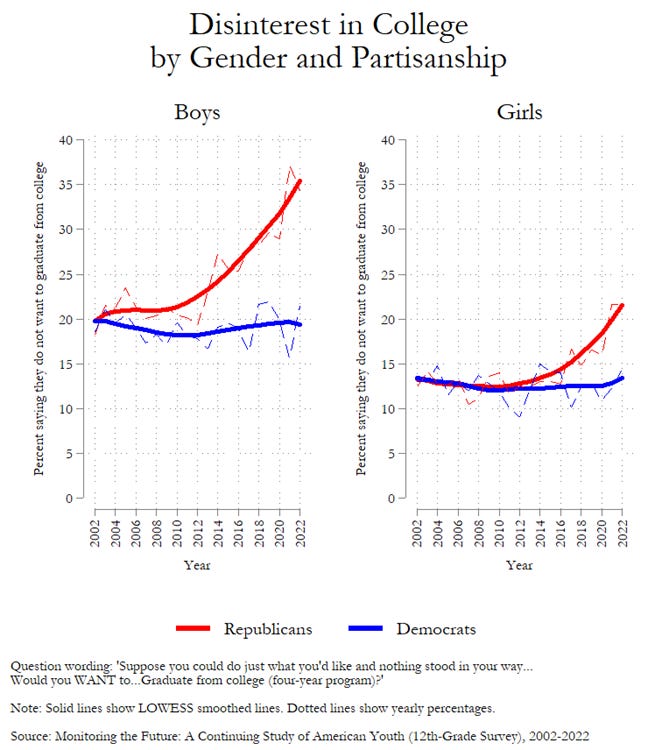

One possibility is that a political realignment has led high schoolers with no interest in attending college to increasingly identify as Republicans instead of Democrats or Independents. There’s no perfect way to explore this possibility with the data provided by Monitoring the Future but it’s worth noting that there’s not any evidence that Republican high schoolers are now coming from families with an aversion to higher education. The percentage of Republican high school students with two college educated parents has increased by 12% since 2002 and by 9% since 2010.

Figure 3 – Parental Education among Republican High School Students

The more likely explanation is that the rising disinterest among Republican high schoolers is a function of the fact that, over the last 15 years, universities have become more ideologically homogenous, more overtly activist, and more monomaniacally focused on power and identity. These changes, and the extensively covered political opposition mobilized in response, have eroded trust in higher education among those on the political right and decreased young conservatives’ desire to attend college.

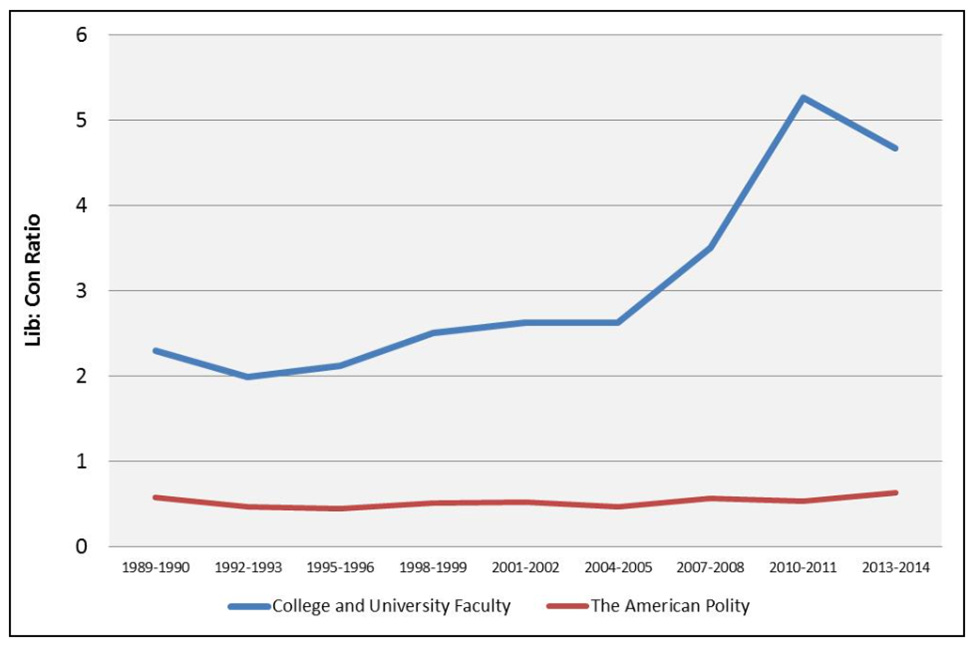

Consider the growing ideological homogeneity of universities. In 1995, the liberal-conservative ratio among faculty members was roughly 2 to 1. By 2010, the ratio was 5 to 1.

Figure 4 - Ideology among Faculty and the General Public (1989-2014)

The most recent data suggests even less political diversity within the professoriate. According to a 2018 survey of liberal arts faculty, for example, the Democrat to Republican party registration ratio was nearly 13 to 1. In 2023, the liberal to conservative ratio among Harvard faculty was 26:1. Nor is the political homogeneity confined to faculty. More than 70% of college administrators and more than 60% of students now identify as liberal.

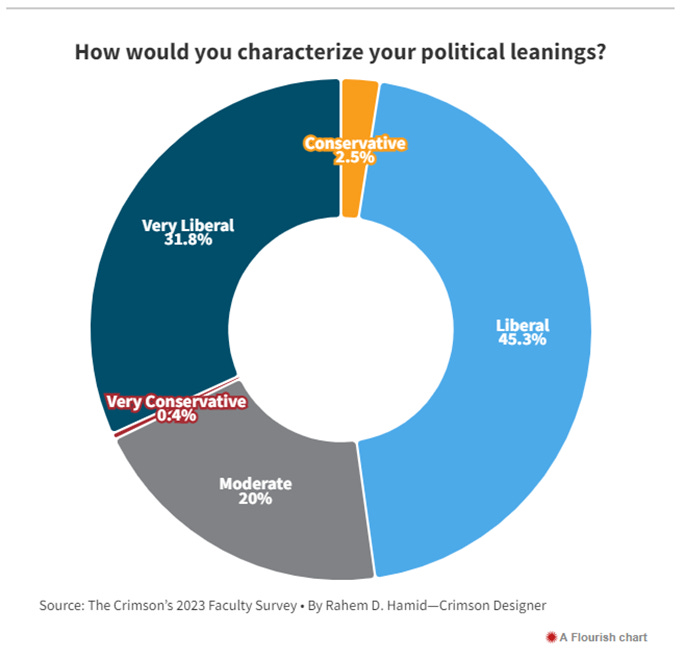

Figure 5 - Self-Reported Ideology among Harvard Faculty Members

It’s not merely the lopsided distribution of political preferences in American universities that may have alienated conservatives, however. It is the increasingly activist nature of campus progressivism. According to a 2020 survey, for example, approximately 40% of social science and humanities faculty members agreed with the statement “I would consider myself as an activist.” As Derek Thompson recently wrote in the Atlantic, “in the past few years, many elite colleges and universities have cast themselves as “anti-racist” and “decolonial” enterprises that hire “scholar activists” as instructors and publish commentary on news controversies, as if they were editorial boards that happened to collect tuition.”

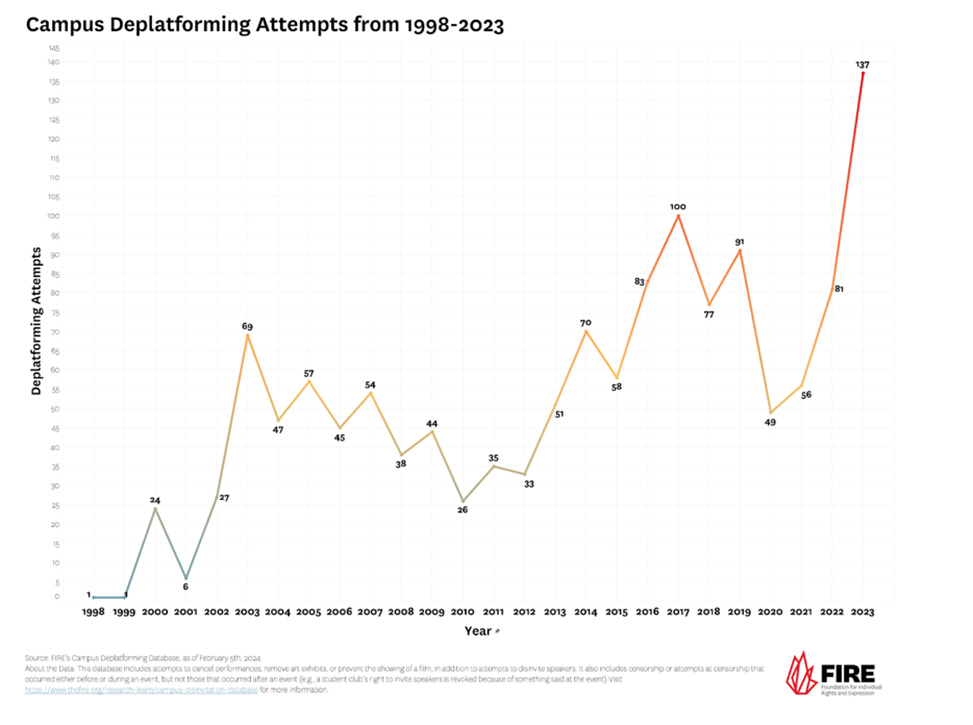

Growing activism from the campus left is also evident among students. According to data from FIRE, there were an average of eight “deplatforming” attempts on college campuses from the political left each year between 1998 and 2012. Since 2013, however, there has been an average of 48 attempts to “deplatform” speakers each year from the political left.

Figure 6 - Deplatforming Attempts on College Campuses (1989-2023)

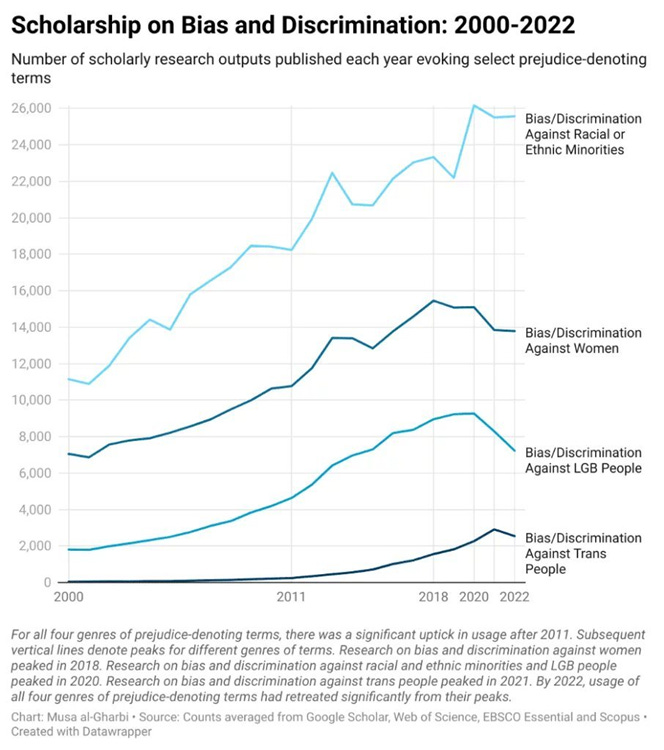

Unsurprisingly, the scholarship produced by universities has shifted along with these broader political changes. A study of 175 million abstracts from scholarly articles published between 1970 and 2020 found that “the prevalence in the academic literature of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse (e.g. racism, sexism, transphobia, Islamophobia, ableism, ageism, fatphobia) has been growing steadily and diffusely since the 1980s but that such prevalence accelerated abruptly after 2010.” While “academic scholarship seems to have passed peak ‘woke,’” the research produced by universities is now far more focused on identity-based bias and discrimination than it was 15 years ago (Figure 3).

Figure 7 – Scholarship on Bias and Discrimination between 2000 and 2022

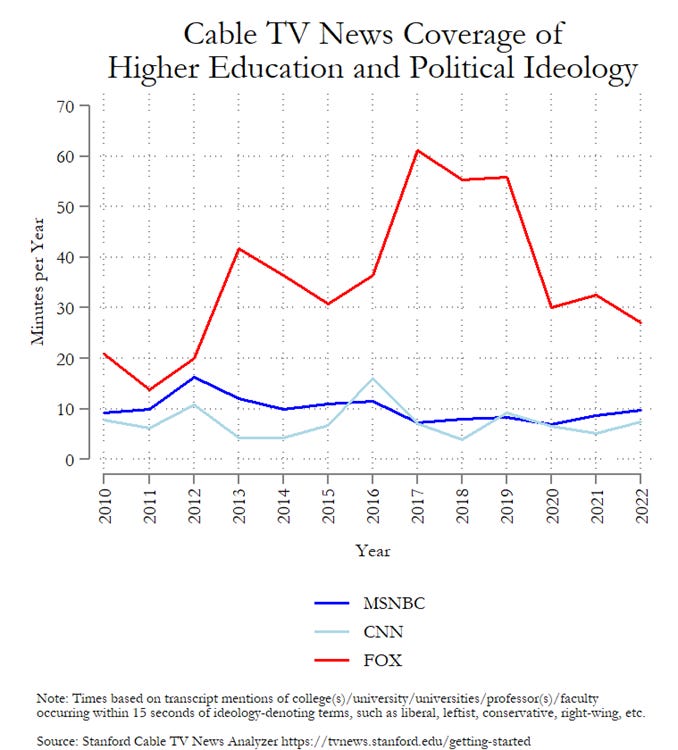

Predictably, these on-campus developments have triggered a reaction from the off-campus political right. Most importantly, Fox News coverage of the politics of colleges and universities (but not MSNBC or CNN coverage) spiked between 2011 and 2013 and, then again, between 2015 and 2017 (Figure 4). This increasing focus on higher education’s leftward shift is undoubtedly underneath some of the right’s growing skepticism toward colleges and universities. As Figure 4 also shows, however, Fox News coverage of campus politics fell significantly after 2017 (the moment when Republican high schooler disinterest in college began accelerating most). This fact suggests that growing distrust and declining interest in higher education among conservatives is not merely a function of Fox News’s coverage.

Figure 8 – Cable TV News Coverage of Higher Education and Political Ideology

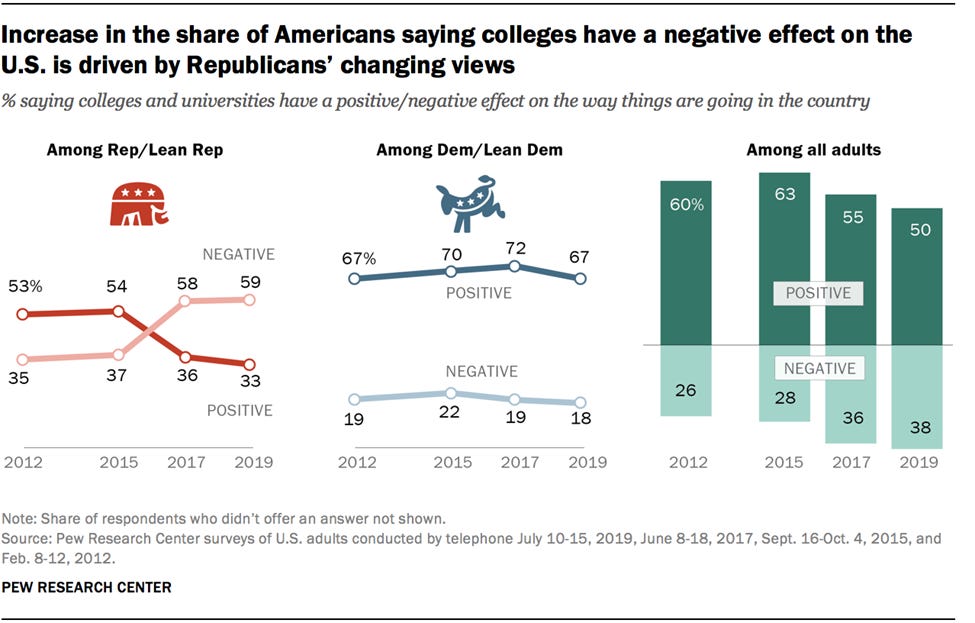

The cumulative impact of all of this has been the evaporation of conservative trust in institutions of higher education. Between 2012 and 2019, the percentage of Republicans saying that colleges have a “negative effect on the way things are going in the country” jumped from 35% to 59%. From 2015 to 2023, the percentage of Republicans expressing “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education fell from 55% to 19%.

Figure 9 - Views of Colleges and Universities by Partisanship

It is also important to note that none of the changes documented above have increased confidence among Democrats (down 9% since 2015) and Independents (down 16% since 2015). And this was all before Claudine Gay’s plagiarism scandal, the campus turmoil immediately following the 10/7 attacks, and the pro-Palestine encampment movement.

Conservative students, exposed to a torrent of news stories highlighting the ideological monoculture of colleges and universities and advised by an increasingly disaffected group of conservative parents, are looking for alternatives to higher education. This is bad news for conservatives, for colleges, and for the country. Conservatives should realize, for example, that universities are still, with some notable exceptions, a strong return on investment and one of the few, proven strategies for upward social mobility. Forgoing higher education will only serve to hurt their economic interests. More broadly, a lost generation of college educated conservatives will leave corporations, media, academia, and government without the deep bench of compelling conservative voices needed to persuasively argue for right of center approaches to public policy problems.

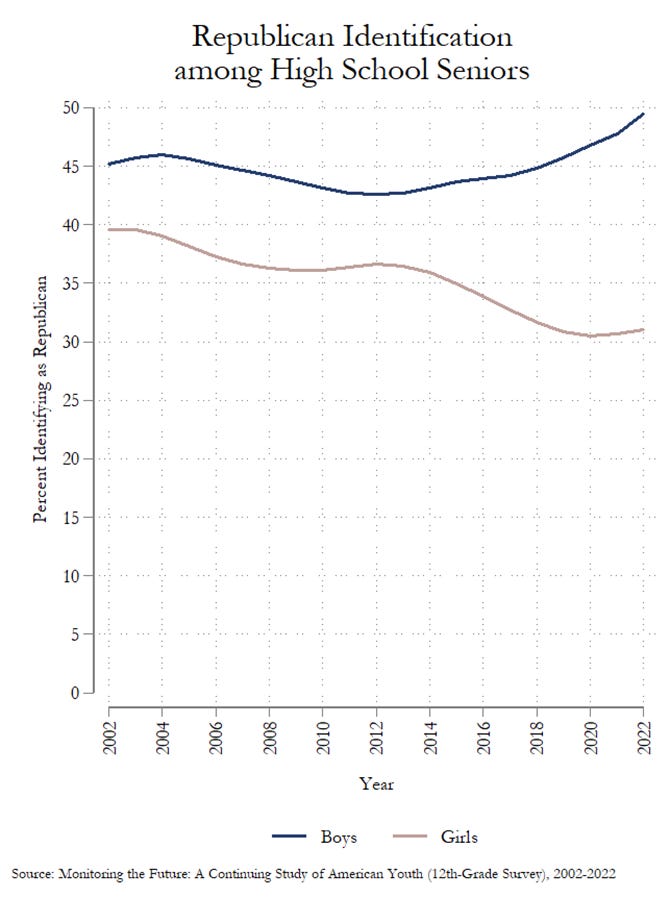

Similarly, institutions of higher education must realize that they cannot continue to willfully alienate a large part of their potential consumer base. Facing low birth rates and declining interest from international students, colleges and universities will not be able to travel along their current course and hope to remain fiscally solvent or socially relevant. Notably, high school boys are becoming more conservative, with nearly 50% of high school boys identifying as Republican in the 2022 Monitoring the Future survey. This demographic is simply too large for colleges to ignore.

Figure 10 - Partisanship among High School Boys

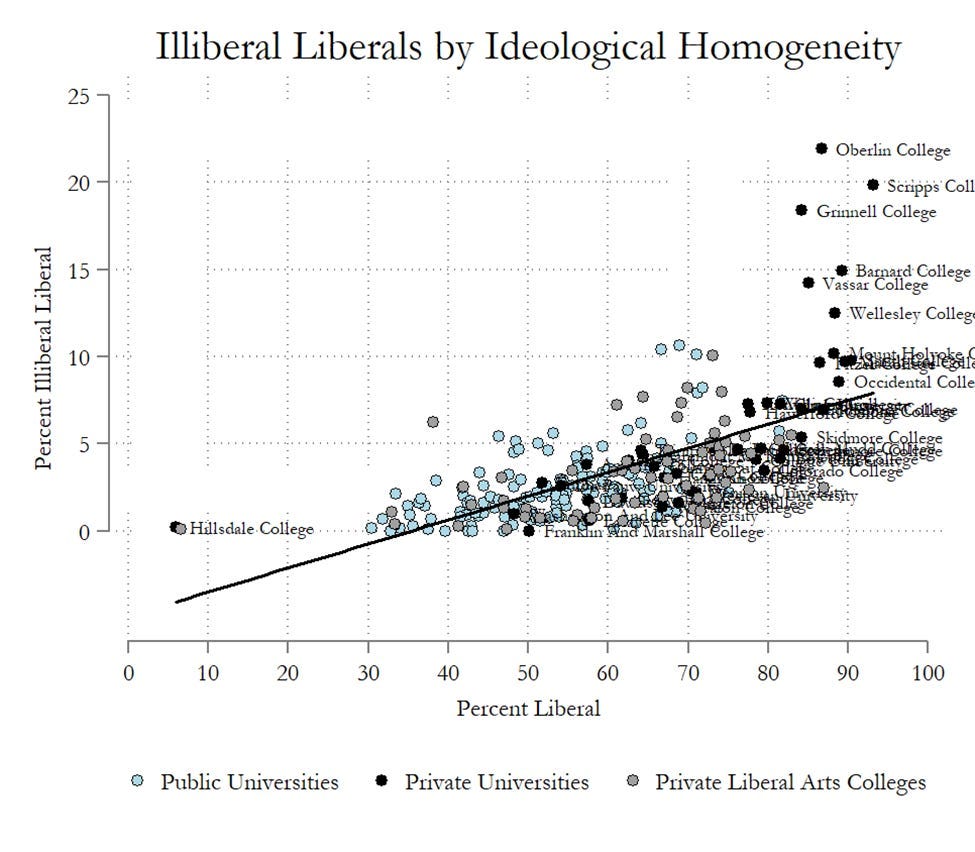

If Republican boys avoid college, it will only further accelerate the trend of growing illiberalism on college campuses. As I have discussed previously, “illiberal liberals” (i.e. self-identified liberals who support all forms of disruptive action to prevent objectionable campus speech and who support deplatforming all controversial conservative speakers) are more numerous on campuses that have less political diversity.

Figure 11 - Illiberal Liberalism and Ideological Homogeneity

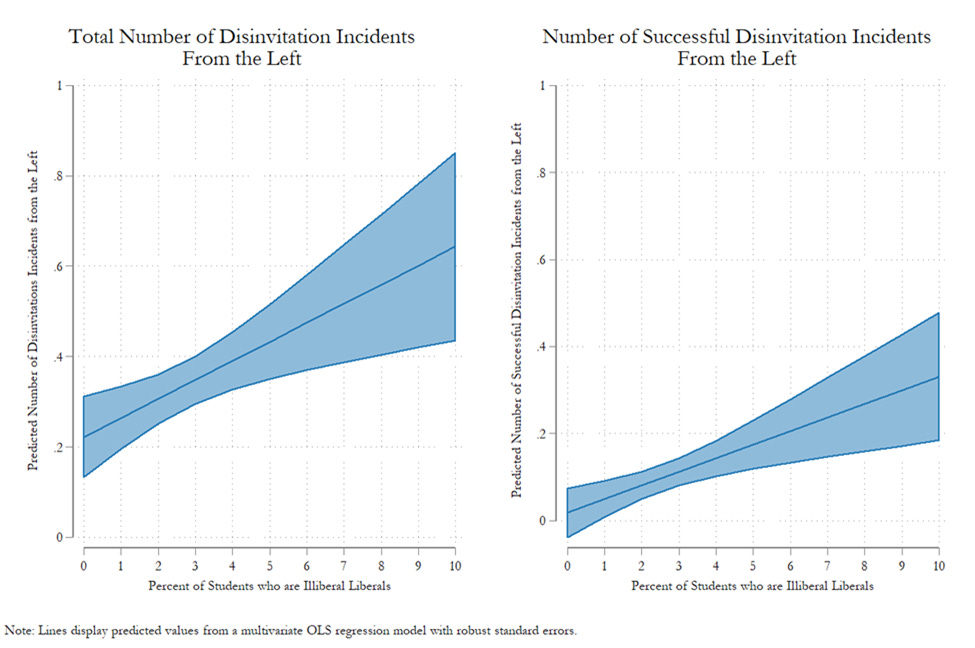

Given that campuses with more “illiberal liberalism” are more likely to deplatform conservative speakers, colleges and universities are in danger of entering a “death spiral” (in which the absence of conservative students leads to more prominent manifestations of the kind of “illiberal liberalism” that further alienates conservative boys and girls).

Figure 12 - Disinvitation Incidents from the Left by Percentage of Illiberal Liberals on Campus

The stakes for the country are even higher. Ideologically captured echo chambers are unlikely to solve “big” problems and they are unlikely to engender trust among a politically diverse population. If conservatives opt out of higher education, colleges and universities will lack the political diversity required to fulfill their core purpose as truth-seeking and truth-disseminating institutions. As Keith Whittington has argued, “Universities make it harder rather than easier to fulfill their core function of advancing knowledge if they nurture orthodoxies and exclude those who might be skeptical of those orthodoxies. Intellectual homogeneity too easily gives rise to intellectual complacency. Intellectual diversity can foster productive dissension.”

Colleges and universities are not the only institutions to lose the trust of the American public broadly and conservatives in particular. They are, however, the most important. Whether the decline is reversible is anyone’s guess but there are three interventions that colleges and universities may want to implement if they care about addressing the problems identified here.

First, colleges and universities should consider adopting the “Chicago Statement” (i.e. the free speech policy produced by the Committee on Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago). Endorsing the idea “the University is committed to free and open inquiry in all matters” and that “it is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive,” would begin rebuilding confidence in universities as “truth seekers” and undermine the notion that they are partisan political actors advancing their own ideological agendas.

Second, colleges and universities should consider addressing their faculty “viewpoint diversity problem.” This need not take the form of ideological quotas imposed during the hiring process but colleges and universities may, as Harvard Professor Tyler VanderWeele has argued, want to “try particularly hard to hire faculty who hold disfavored or controversial views when those views are held by a large portion of the population, have not been clearly refuted, and influence culture and policy.” Eliminating mandatory DEI statements in faculty hiring, which often serve as an ideological litmus test, is also an important step in this regard.

Finally, colleges and universities may want to heed the Kalven Report’s reminder that they are “the home and sponsor of critics,” not critics themselves.

I think you are overestimating the economic impact of this on conservatives. If you look at the data, graduates in STEM fields are still on the rise, it is only humanities that are having a decrease in graduates. My inference is that the conservatives that are not going to college are not ones that were considering STEM, but conservatives that were planning on going into humanities.

This makes a lot of sense because most people go into humanities programs because they think they would enjoy studying it or were hoping to become tenured professors. But conservatives now rarely enjoy learning humanities in college because the classes are very left leaning. They also assume they will never be able to become tenured professors, due to discrimination. I think it is completely rational for a conservative that is interested in humanities to go to trade school instead of getting a degree that will only let them become teachers.

How many 17 year old Republicans are there?