Discover more from The Missing Data Depot

Higher Education's "Illiberal Liberalism" Problem

Asymmetrical illiberalism (i.e. that illiberal liberals vastly outnumber illiberal conservatives on college campuses) is a problem for higher ed. This post offers a data-driven explanation of why.

Liberalism - Classical and Modern

The Growing Tension Between Political Tolerance and Equality

According to Francis Fukuyama, “The most fundamental principle enshrined in [classical] liberalism is tolerance.” For Fukuyama and others, the essence of tolerance is the “willingness to put up with, or to permit, the [speech], actions or practices of others, which one disapproves of and which one otherwise would seek to prohibit or prevent from occurring.” One of the defining features of illiberalism, then, is political intolerance or, put differently, an unwillingness to permit the speech, actions, or practices that one disapproves of.

The so-called “classical liberalism” described here is distinct, of course, from the “liberalism” of the modern American left (which is most commonly understood to mean support for “activist government to help the poor and the middle class—taxes, transfer programs, and regulation—plus a concern for civil rights and equality”). Throughout the late 20th century, however, this distinction meant very little for most Americans; the vast majority of people who identified as “liberal” strongly endorsed the values implied by both the “classical” (e.g. free expression and political tolerance) and “modern” (e.g. civil rights and equality) forms of liberalism.

A growing emphasis on the importance of equality and an ongoing reevaluation of the harms associated with free speech and tolerance, however, has recently led many self-identified liberals to abandon the “classical” elements of their liberalism. Some of these so-called “modern liberals” have even come to view free speech and tolerance as impediments to “the correction of unjust distributions produced by the market and the dismantling of power hierarchies based on traits like race, nationality, gender, class, and sexual orientation.” As Henry Louis Gates explained in a 1993 article entitled “Let Them Talk: Why Civil Liberties Pose No Threat to Civil Rights,” concerns about “hate speech” have caused many on the left “to rethink their allegiance to the very amendment that licensed the protests and the agitation that galvanized the nation in a recent, bygone era.” Now, Gates laments, “Civil liberties are regarded by many [on the left] as a chief obstacle to civil rights.”

The emergence of equality as a substantial counterweight to tolerance has encouraged the proliferation of a previously rare species of political animal: the “illiberal liberal.” Although countless commentators from across the political spectrum in recent years have complained about growing illiberalism among liberals and attempted to draw clear rhetorical boundaries between proponents of classical and modern liberalism (e.g. the distinction between “liberals” and “leftists”), there have been few systematic attempts to pin down exactly how common this insurgent variety of illiberalism is among liberals and what its consequences are.

Illiberalism on College Campuses - An Overview

This post attempts to expand our understanding of “illiberal liberalism” (i.e. the combination of intolerant attitudes towards speech with support for “activist government” and civil rights) by leveraging the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s (FIRE) unique data on American college students. Specifically, I ask: how widespread is “illiberal liberalism” on college campuses today, and does this “illiberal liberalism” matter for the quality of campus speech environments?

The data presented below tell a clear story: American higher education has a small but consequential “illiberal liberal” problem. Self-identified liberals who support all forms of disruptive action (including violence) to prevent objectionable campus speech and who support deplatforming all controversial conservative speakers make up approximately 3% of college students nationally and more than 10% of students at many of the nation’s top “liberal arts” colleges. This problem appears to be driven, in part, by a lack of exposure to alternative viewpoints. As I document below, the share of students who are “illiberal liberals” is highest in the places where ideological diversity is lowest.

Although the 3% and 10% numbers might appear underwhelming at first glance, it is important to remember that it only takes a tiny handful of committed activists to successfully disrupt a campus speech or intimidate students, faculty, and staff into silence. Indeed, some research shows that the active participation of 3.5% of a given population can produce profound social, political, and economic change within that population’s community.

Consistent with the idea that small groups can have large impacts, I find that even marginal increases in the number of illiberal liberals attending a college have significant and negative consequences for the quality of that campus’s speech environment. As I show below, for instance, it is the percentage of “illiberal” liberal students on campus – not the percentage of liberal students in general – that seems to encourage deplatforming efforts targeting insufficiently progressive speakers. The evidence presented here also suggests that the percentage of “illiberal” liberals on a campus may lead the campus to experience more protests, marches, walkouts, classroom controversies, and disruptions.

This post will focus primarily on “illiberal liberalism.” The reason for this narrow focus is that there is almost no evidence that “illiberal conservatives” exist anywhere on college campuses. In FIRE’s nationally representative sample of more than 55,000 students, only 40 students (less than one-tenth of a percent) were self-identified conservatives who view all forms of disruptive action as acceptable and support deplatforming liberal speakers. On college campuses, in other words, illiberalism is solely an affliction of the left.

How to talk young liberals out of their illiberalism is one of the primary challenges facing universities. While the evidence presented here does not offer any specific advice for persuading “modern liberals” about the virtues of “classical liberalism,” it does identify the scope, location, and consequences of higher education’s illiberalism problem. By doing so, I hope this post can help better focus the much-needed and long-overdue efforts now gathering steam to reform the nation’s universities.

The Political Ideology of College Students

Every year since 2020, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) has conducted a vast, nationwide survey of college students as part of their efforts to rank the free speech climates of American universities. The 2023 survey included 55,000 enrolled students at 254 colleges around the country.

In addition to a battery of demographic (race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) and speech-related questions (discussed further below), FIRE’s survey asked students to describe their political beliefs. To no one’s surprise, the results show that most college students place themselves on the political left, with 58.8% describing their political views as “liberal” or “democratic socialist” and only 24.4% describing their views as “conservative” or “libertarian.” Interestingly, very few (16.7%) of college students label themselves as “moderate.” This distribution of political identification makes college students distinct from the American public broadly and non-college attending members of Gen Z (both of whom are less liberal and more moderate).

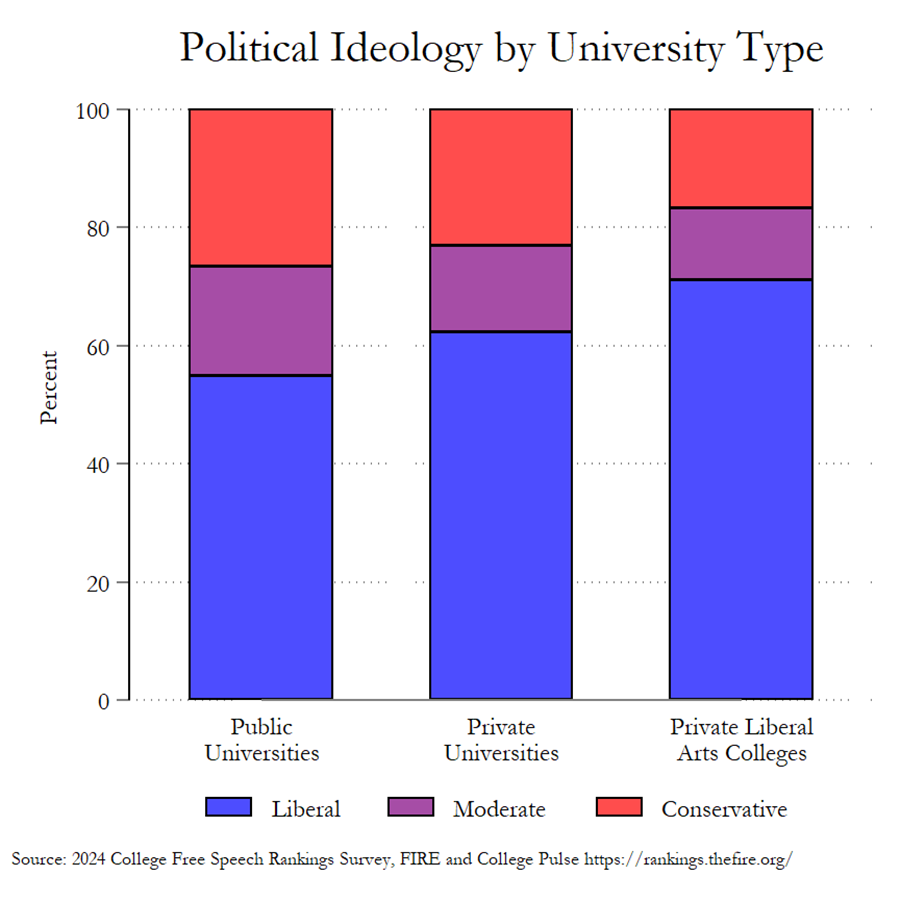

Figure 1 – Self-Reported Ideology by School

The national-level picture painted above masks significant cross-campus variation in political ideology, however. On 22 of the 254 campuses surveyed by FIRE, more than 80% of students identified as liberal (Figure 1). There were even two schools – Hillsdale College and Liberty University – where more than 80% of students identified as conservative.

Figure 2 – Self-Reported Ideology by School Type

A quick glance at the schools listed in the left-hand panel of Figure 1 suggests the distribution of political beliefs varies between universities and liberal arts colleges. As Figure 2 makes explicit, private liberal arts colleges have far more liberal students (72.9% of the student population) than private or public universities (63.1% and 53.9%, respectively).

As we start thinking about the prevalence and consequences of student “illiberalism” it is important to keep this school-level variation in mind. The potential population of “illiberal liberals” across college campuses generally and private liberal arts schools in particular is much greater than the potential population of “illiberal conservatives.” Even if liberals and conservatives are equally prone to illiberalism, the vastly greater number of liberals on college campuses will mean that their illiberalism is more consequential than that of conservatives.

Illiberalism among College Students

Measuring Illiberalism in the FIRE Survey

As mentioned above, illiberalism can be defined as political intolerance or, put differently, an unwillingness to permit the speech, actions, or practices that one disapproves of. When defined in this way, the FIRE survey includes two batteries of questions that provide useful proxies for measuring how strongly students subscribe to liberal norms of political tolerance in response to offensive (yet constitutionally protected) speech.

First, FIRE’s survey asked students a series of questions to assess how tolerant they were of controversial speakers. Specifically, students were asked whether the following three speakers who had previously espoused controversial liberal ideas should be allowed to speak on campus:

The Second Amendment should be repealed so that guns can be confiscated.

Structural racism maintains inequality by protecting White privilege.

Religious liberty is used as an excuse to discriminate against gays and lesbians

Students were also asked whether the following three speakers who had previously espoused controversial conservative ideas should be allowed to speak on campus:

Abortion should be completely illegal.

Transgender people have a mental disorder.

Black Lives Matter is a hate group.

FIRE’s question asked students to state their opinion on whether these speakers should be allowed on campus independent of their opinions about the speaker’s message (“Student groups often invite speakers to campus to express their views on a range of topics. Regardless of your own views on the topic, should your school ALLOW or NOT ALLOW a speaker on campus who promotes the following idea?”). In other words, the question was attempting to measure how principled students were with respect to speech on campus.

Second, the FIRE survey also asked respondents “How acceptable [always, sometimes, rarely, never] would you say it is for students to engage in the following action to protest a campus speaker?”:

Shouting down a speaker to prevent them from speaking on campus.

Blocking other students from attending a campus speech.

Using violence to stop a campus speech.

These two groups of questions can be combined with self-reported political ideology to categorize a student as an “illiberal liberal” or an “illiberal conservative.” To be more precise, an “illiberal liberal” can be defined as a student who meets each of the following four criteria:

Identifies themselves as a “liberal” or a “democratic socialist.”

Says all three forms of disruptive action to prevent a campus speaker are “always,” “sometimes,” or “rarely” “acceptable.”

Says all three of the controversial liberal speakers described in FIRE’s survey should be allowed to give a speech on campus.

Says all three of the controversial conservative speakers described in FIRE’s survey should NOT be allowed to give a speech on campus.

Similarly, an “illiberal conservative” can be defined as a student who meets each of the following four criteria: :

Identifies themselves as a “conservative” or a “libertarian.”

Says all three forms of disruptive action to prevent a campus speaker are “always,” “sometimes,” or “rarely” “acceptable.”

Says all three of the controversial conservatives described in FIRE’s survey should be allowed to give a speech on campus.

Says all three of the controversial liberal speakers described in FIRE’s survey should NOT be allowed to give a speech on campus.

In short, an illiberal is both a “speech disruptor” (i.e. someone who endorses all forms of disruptive action to prevent speech) and an “out-group censor” (i.e. someone who favors speech rights for all of their ideological allies but opposes speech rights for all speakers from the other side of the political spectrum).

This approach to operationalizing “illiberalism” is exceedingly (and intentionally) stringent. For example, a liberal student expressing support for non-violent but illiberal tactics to limit speech (i.e. someone who endorsed shout-downs and blockades but not violence) would not be classified as an “illiberal liberal” under these rules. Similarly, if a liberal student supports allowing even one of the three hypothetical conservative speakers the opportunity to deliver a campus speech, they will not be classified as an “illiberal” using this approach. Even a liberal who says that one of the three hypothetical liberal speakers should NOT be allowed to speak on campus will fail to qualify as “illiberal” with these criteria.

As such, the data presented below constitute a “floor-level” or “bare minimum” estimate of illiberalism on college campuses. A looser definition would find much higher overall levels of illiberalism on the left and the right.

“Speech Disruptors” and “Out-Group Censors” on College Campuses

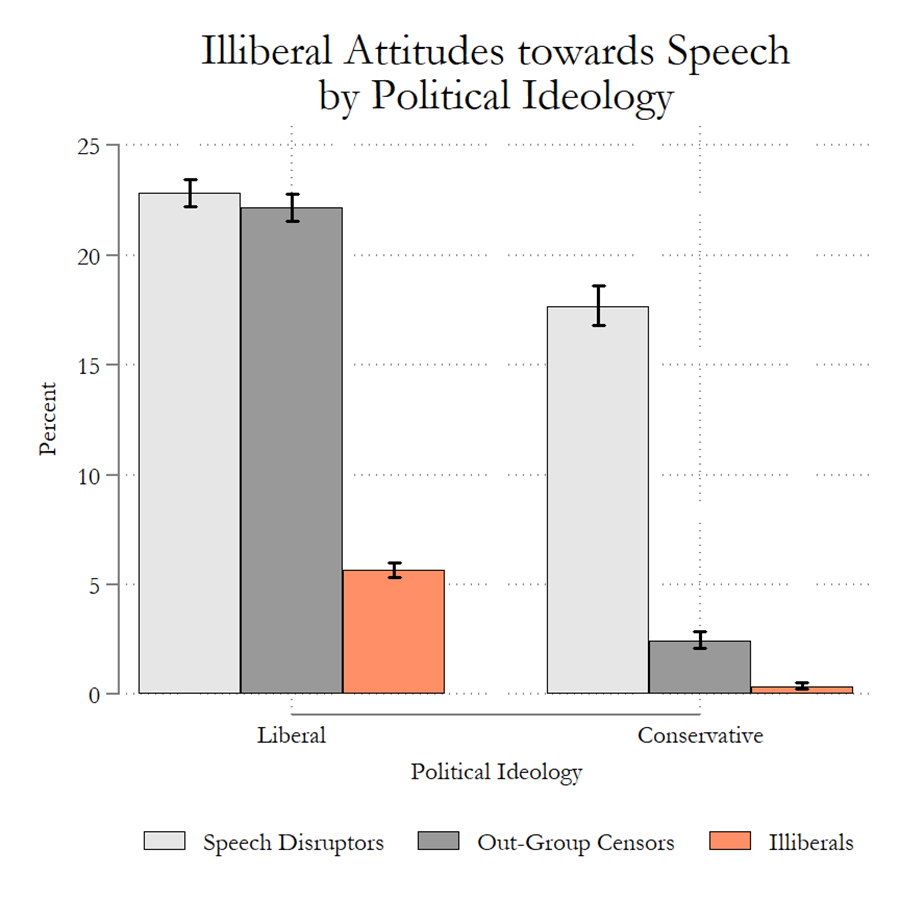

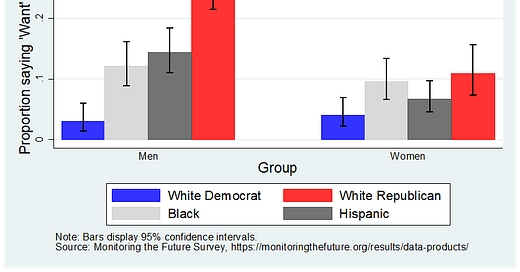

Before identifying how many students are “illiberal” it is useful to explore how many students are, separately, “speech disruptors” and “out-group censors.” As Figure 3 shows, nearly one in four liberal college students are “speech disruptors,” meaning they endorse all forms of disruptive action (i.e. shout-downs, blockades, and violence) to prevent campus speech. A similar percentage (22.2%) are also “out-group censors” (i.e. students who would like to prevent all controversial conservative speakers from appearing on campus but would like to allow all controversial liberal speakers).

Figure 3 – Illiberalism by Self-Reported Ideology

Figure 3 also shows that conservative college students are significantly less likely to hold illiberal attitudes toward speech than liberal college students. While nearly one in four liberals is a “speech disruptor,” only 17.7% of conservatives are. More importantly, liberal college students were almost ten times more likely to qualify as an “out-group censor” than conservative college students (22.2% to 2.4%).

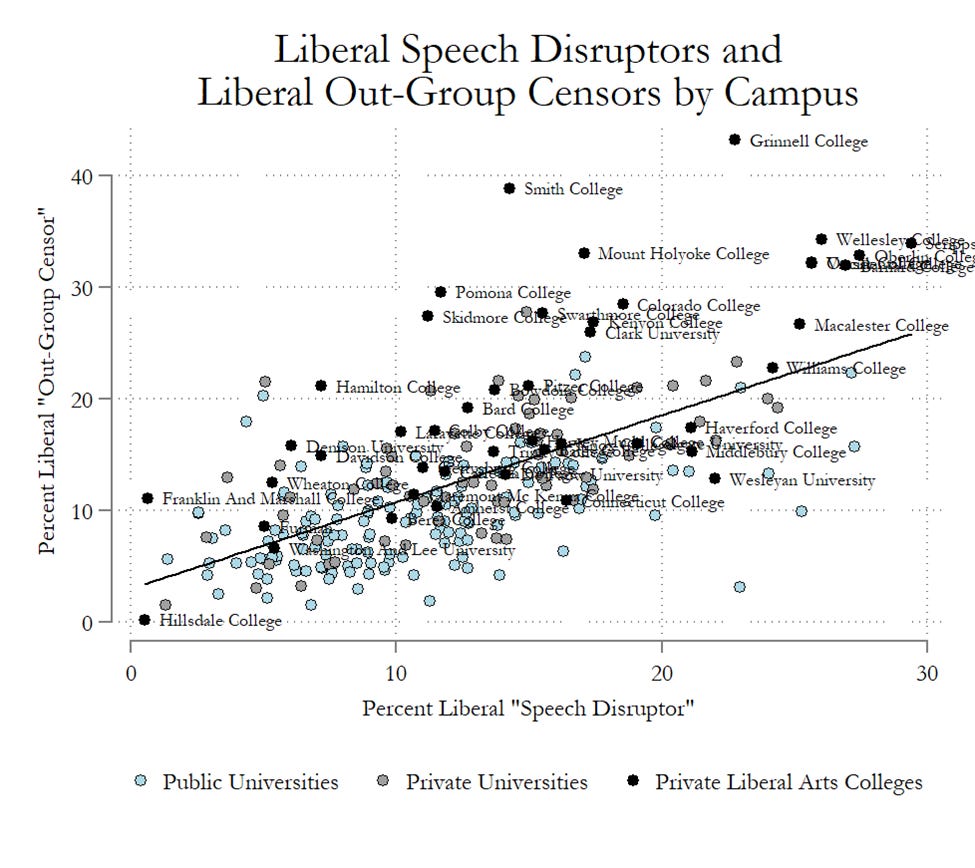

Figure 4 – Liberal “Speech Disruptos” and Liberal “Out-Group Censors” by School

Liberal “speech disruptors” and “out-group censors” are not equally distributed across college campuses. As Figure 4 shows, there were ten schools where more than one-fourth of students were liberal “speech disruptors” and five schools where more than one-third of students were liberal “out-group censors.” More generally, the percentage of students who are liberal “speech disruptors” is highly and positively correlated with the percentage of students who are liberal “out-group censors” (r=.633, p=.00).

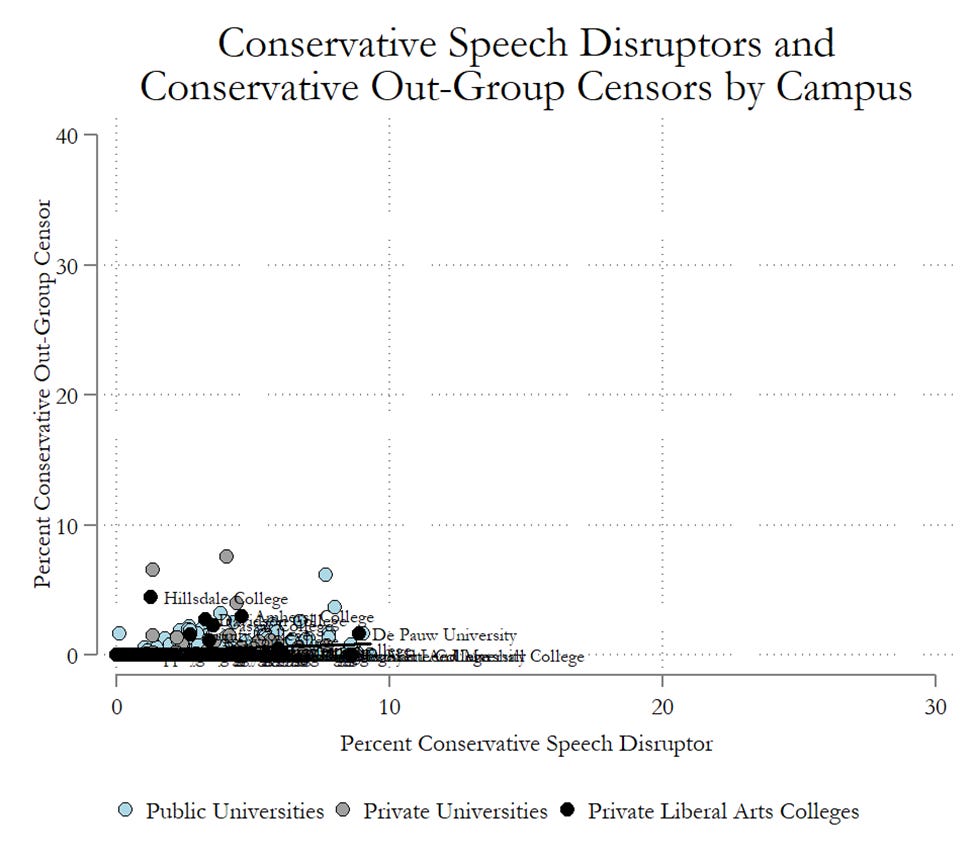

Figure 5 –Conservative “Speech Disruptos” and Liberal “Out-Group Censors” by School

The distribution of conservative “speech disruptors” and “out-group censors” presented in Figure 5 tells a much different story. While there were 148 universities where more than 10% of the student population qualifies as a liberal “speech disruptor,” there was not a single school in the country where conservative “speech disruptors” make up more than 10% of the student population. Similarly, more than half of the colleges and universities surveyed by FIRE (133 out of 254) had 0 conservative “out-group” censors and there was not a single school where conservative “out-group censors” exceeded 10% of the student body. By contrast, every one of the colleges and universities surveyed by FIRE had at least one liberal “out-group censor” and more than half (143 out of 254) have student populations composed of more than 10% liberal “out-group” censors.

In short, college-level “speech disruption” and “out-group censorship” are problems concentrated entirely on the political left.

Illiberal Conservatives

How many college students are “illiberal” conservatives (i.e. they are both “speech disruptors” and “out-group censors”)? Based on the above discussion, it should come as no surprise that “illiberalism” is nearly non-existent among college conservatives. Out of the more than 11,000 conservative college students in FIRE’s survey, there were only 40 (less than one-half of one percent) that can be classified as “illiberal” (i.e. students that endorse all forms of disruptive action and support bans for controversial speakers only when those speakers are from the other side of the political spectrum).

Unsurprisingly, therefore, illiberal conservative students were completely absent from 218 of the 254 schools included in FIRE’s survey. In the remaining 36 schools, illiberal conservatives were less than 1 in 200 students.

In both a substantive and statistical sense, illiberal conservatives are so rare on college campuses today that it makes very little sense to even discuss them as a distinct group. The rest of this post, therefore, is devoted to discussing a far larger and far more consequential source of illiberalism on college campuses: liberal students.

Illiberal Liberals

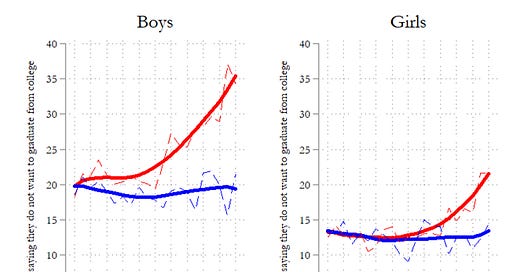

How many college students are “illiberal” liberals (i.e. they are both “speech disruptors” and “out-group censors”)? Taking the two measures of illiberalism (“speech disruption” and “out-group censorship”) together, more than 5% of left-leaning college students can be classified as “illiberal.”

Liberal students, then, have a much greater tendency towards illiberalism than conservative students. When coupled with the fact that there are far more liberal students than conservative students, this increased propensity towards political intolerance produces a vast disparity in the number of illiberal liberal students and illiberal conservative students. Specifically, illiberal liberals make up 2.9% of all college students while illiberal conservatives make up only .08%.

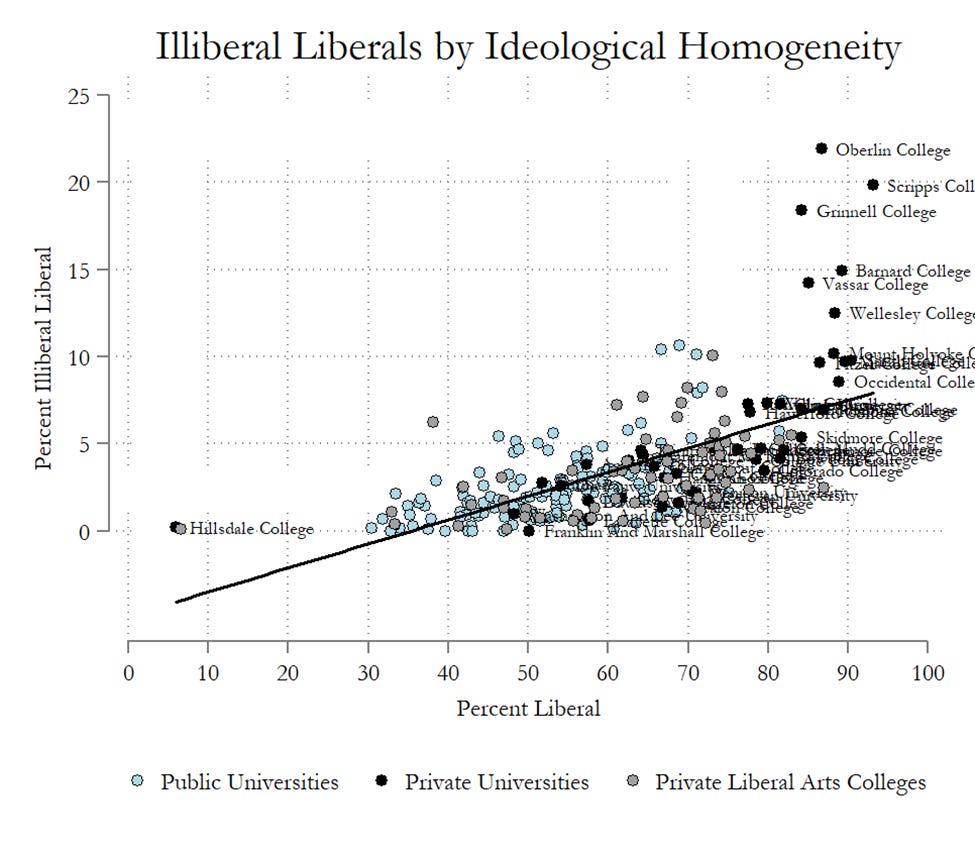

As already suggested by the plot in Figure 4, there’s wide variation in illiberal liberalism across campuses. While more than 15% of the student body at some schools (e.g. Oberlin College, Scripps College, Grinnell College) are “illiberal liberals,” 0% of students at other schools meet the requirements for “illiberal liberalism” spelled out above (e.g. University of Mississippi, Montana State University, Northern Arizona University).

Figure 5 - Top 20 Schools Ranked by Percentage of Illiberal Liberal Students

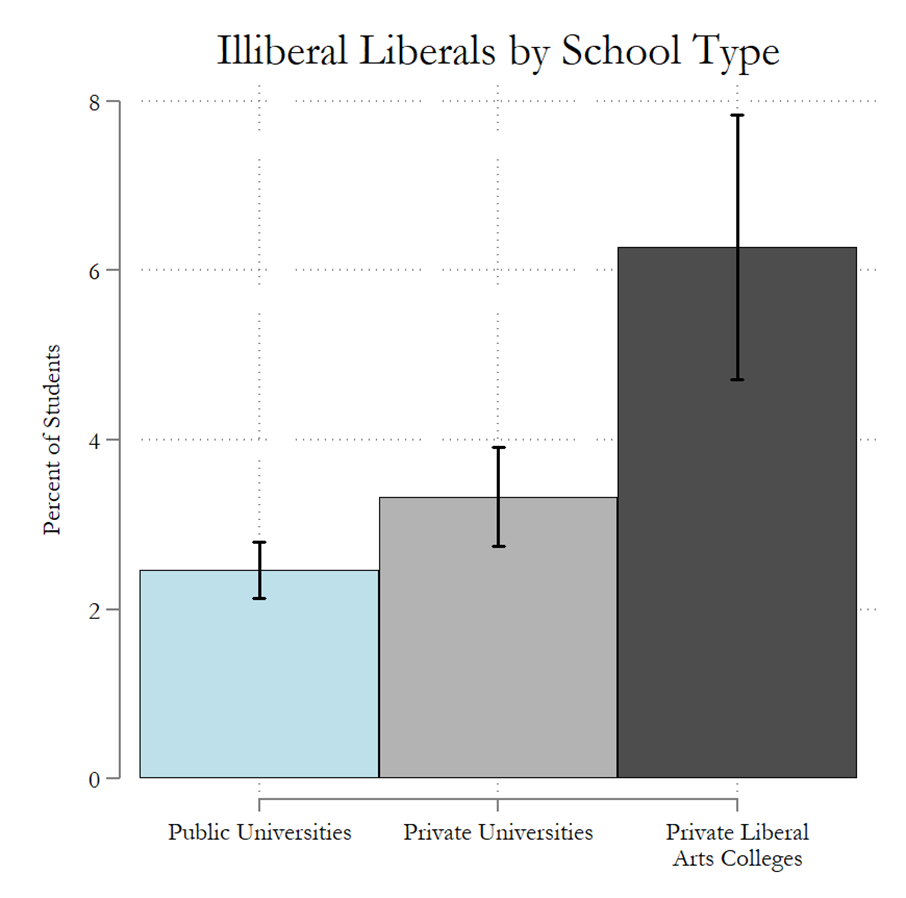

Figure 5 shows the top 20 schools for “illiberal” liberalism in the country. Ironically, “illiberal” liberal students are largely creatures of liberal arts colleges, with more than half the schools in the Top 20 of “illiberal” liberalism being liberal arts colleges. More generally, liberal arts colleges have a significantly larger percentage of “illiberal” liberal students than public or private universities (Figure 6).

Figure 6 -Percentage of Illiberal Liberals by School Type

The relatively high rate of “illiberal” liberalism at liberal arts colleges is likely connected to the extreme lack of ideological diversity on these campuses. As Figure 2 shows, students at liberal arts colleges are far more liberal than students at public or private universities. Just because a school has more liberal students should not necessarily mean that it will have a larger percentage of illiberal liberals. Yet, as Figure 7 shows, campuses where liberals are a greater share of the student body also have a greater share of illiberal liberals (r=.63, p=.00). More ideological homogeneity seems to produce more illiberal liberalism.

Figure 7 - Illiberal Liberalism and Ideological Homogeneity

Does Illiberal Liberalism Matter?

Disinvitation Incidents

The big question about “illiberal liberalism” is whether it matters for what happens (or doesn’t happen) on college campuses. One way to answer this question is to assess the relationship between how much illiberal liberalism there is on a campus and how frequently it experiences liberal-led efforts to deplatform insufficiently progressive speakers.

FIRE’s Campus Disinvitation database has tracked the number of so-called “disinvitation incidents” (i.e. “controversies on campus that arise throughout the year whenever segments of the campus community demand that an invited speaker not be allowed to speak”) for more than two decades. For each of the database’s 576 listed “disinvitation incidents” since 1998, FIRE has coded whether the deplatforming attempt came “from the left of the speaker” or “from the right of the speaker” and whether it was successful in revoking the invitation or disrupting the speech.

Using FIRE’s disinvitation data from the last three years, I analyzed whether campuses with more “illiberal” liberals experience a larger number of illiberal attempts to limit speech offensive to progressives. More specifically, I ran an OLS regression model (with robust standard errors) predicting a campus’s number of total and successful disinvitation incidents coming from the political left based on its percentage of liberal students, its percentage of “illiberal” liberal students, and a range of other variables measuring features of its student population (including its racial, gender and religious composition).

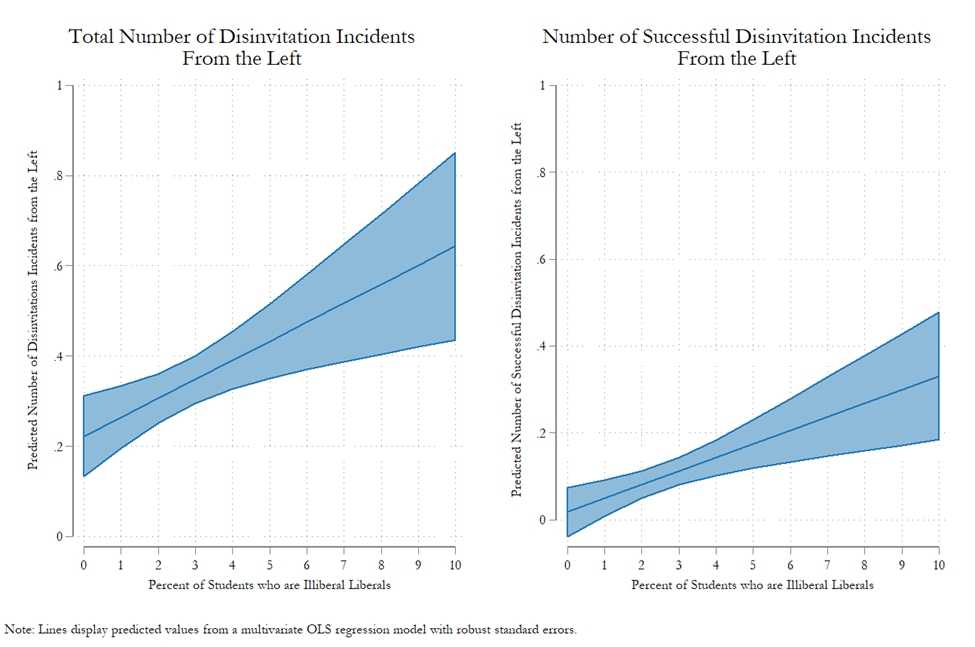

Figure 8 illustrates the results of this analysis by presenting the predicted number of total (left-hand panel of Figure 8) and successful (right-hand panel of Figure 8) disinvitation incidents coming from the political left for different percentages of liberal students and illiberal liberal students (holding all other variables constant at their means).

Figure 8 - Disinvitation Incidents from the Left by Percentage of Illiberal Liberals on Campus

The impact of illiberal liberalism on disinvitation incidents is unambiguous: campuses with more illiberal liberals are significantly more likely to experience successful and unsuccessful disinvitation incidents originating from the left. As Figure 8 shows, increasing the percentage of students who are illiberal liberals from 0% to 10% is predicted to triple the number of disinvitation incidents from the left overall and quadruple the number of successful disinvitation incidents from the left. In other words, the prevalence of illiberal liberals on a campus is a major factor in determining the frequency and outcome of attempts to deplatform non-progressive speakers on that campus.

It is crucial to point out here that the number of campus disinvitation incidents coming from the political left (whether successful or not) is unrelated to campus liberalism more generally. In the multivariate OLS regression models described above, the percentage of students on each campus who self-identify as liberal was not a statistically significant influence on the total number of disinvitation incidents from the left (b=.00, p=.33) or on the number of successful disinvitation incidents from the left (b=.00, p=.47) after controlling for the campus’s illiberal liberalism. Together, these findings should help clarify that campus “cancel culture” is a consequence of the growing number of “illiberal liberals” found on campus and not a consequence of left-wing, ideological homogeneity in higher education alone.

It is also important to be clear about the limitations of the FIRE disinvitation data. Disinvitations incidents can only occur if an invitation has been issued in the first place. One way that illiberal liberals might influence campus speech environments is to prevent disagreeable speakers from being invited at all.

Consider, for example, the most illiberally liberal college in the country: Oberlin College. While nearly 22% of students at Oberlin qualify as “illiberal liberals,” the campus has not experienced a single disinvitation incident since the attempted deplatforming of Christina Hoff Sommers in 2015. Rather than concluding that campus illiberal liberalism is not actually as influential as we originally assumed, it is probably best to interpret the lack of disinvitation incidents at Oberlin as evidence that illiberal liberalism works to constrain campus speech environments in many ways that are not captured by the simple number of disinvitation incidents (e.g. discouraging students and faculty from even considering hosting a speech by a right of center speaker on campus). To state all of this differently, the findings from the disinvitation database capture only one, very narrow dimension of illiberal liberalism's influence on college speech environments.

Incidents of Disruption

In an attempt to broaden my assessment of the impact of illiberal liberalism on campus politics, I also built upon the recent work of Nathan Honeycutt and Andrea Lan. In a fascinating and carefully executed study of recent campus “incidents” related to the Israel-Palestine conflict, Honeycutt and Lan show that protests, marches, walkouts, classroom controversies, disruptions, denouncements of university officials, and vandalizations were more common at “colleges where students are more accepting of illiberal forms of protest and where students have greater difficulty discussing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

Figure 9 - On-Campus Incidents Related to the Israel-Palestine Conflict by Percentage of Illiberal Liberals on Campus

Using Honeycutt and Lan’s measure of campus incidents related to the Israel-Palestine conflict, I ran a logistic regression model with the same set of variables included in the disinvitation analysis above. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the results (Figure 9) show that campuses with a larger percentage of students who are illiberal liberals had a significantly higher probability of experiencing a disruptive, on-campus incident connected to the Israel-Palestine conflict between October 7 and November 6, 2023. Although the impact of illiberal liberalism on incidents for other issues might be more muted, these results are consistent with the possibility that more illiberal liberalism at a school produces more contentious campus political environments overall.

Concluding Thoughts

The above analyses are likely to significantly underestimate the extent and consequences of illiberal liberalism on college campuses. As discussed above, I adopt the strictest possible definition of illiberalism (requiring support for both “speech disruption” and “out-group censorship”) and I rely primarily on “disinvitation incidents” to assess illiberal liberalism’s impact (thereby missing the chilling effect it undoubtedly has on other dimensions of a campus’s speech environment). Put differently, as concerning as the above findings are, they are probably minimizing the significance of illiberal liberalism on college campuses.

Even with this in mind, the evidence presented here has documented a concerning asymmetrical illiberalism on college campuses. The asymmetry is largest on the campuses of private liberal arts colleges but its consequences are felt at universities around the country. Any attempt to address the campus “free speech crisis” and create healthier intellectual climates at our colleges and universities will need to address the small but significant problem of illiberal liberalism documented here.

If you can't contemplate why someone might have a different point of view, why would you let them speak?

Once you've got all the answers, why ask questions?

Once you've got a certain set of taboos, when you've been taught that only evil people can believe these things for evil reasons, then its inevitable your going to build an intellectual construct where they have to be destroyed.

I don't mean to preach relativism. Relativism lost pretty hard to illiberal liberalism. Something more like discerning humility.

This isn't just a problem in education, entertainment has this as does big tech.