Big Tech's Surprisingly Weak Case for Affirmative Action

Google, Meta, and Apple are trying to persuade the Supreme Court to allow race-based affirmative action by referencing a small and deeply flawed group of studies

Affirmative Action in the Supreme Court

On October 31, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in two cases about the use of race-based affirmative action at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. In deciding these cases, the Court may choose to end the decades-long practice of allowing universities to grant preferential treatment to some applicants on the basis of their race or ethnicity.

As part of the Supreme Court’s consideration of a case, interested parties (frequently referred to as “amicus curiae”) are allowed to author and submit briefs that offer information, expertise, or insight relevant to the issues in the case. In August, Google, Meta Platforms Inc., Apple Inc., HP, Inc. and more than 70 other major US-based companies filed an amicus curiae brief with the US Supreme Court in support of affirmative action programs being challenged at Harvard and the University of North Carolina.

In this post, I’m going to examine the arguments presented in this amicus curiae brief. As I will demonstrate below, the brief attempts to use social science research on workplace diversity to make the case for the continued use of race-based admissions in American universities. Unfortunately for Amici (i.e. the companies behind the brief), the cited social science research makes an incredibly shallow and weak case for affirmative action. Despite the fact that decades of research have attempted to demonstrate the benefits of racial diversity in the workplace, the brief can only summon a small collection of flawed studies that fail to demonstrate: (1) increasing diversity above the levels currently found in Amici’s companies will produce meaningful business benefits; and (2) allowing universities to continue with an illiberal and unpopular policy is the only (or even the best) means of achieving higher levels of racial diversity.

As always, my hope is that this post will provide a model for how to critique arguments that use social science research as a means of advancing controversial positions on matters of public policy.

Affirmative Action in the People’s Court

In the 1960s and early 1970s, affirmative action was justified on the grounds that it would serve as a kind of reparation for the harms imposed by America’s long-standing system of institutionalized discrimination against African Americans.1 Even at the outset, this argument rested on a somewhat shaky moral foundation given that the beneficiaries of preferential treatment were rarely the actual victims of discriminatory action and that those who paid the costs were often not those who engaged in the discriminatory conduct. Nevertheless, this “reparational” or “remedial” approach to affirmative action for African Americans maintained a sufficient level of public support to preempt a strong enough public backlash to overturn it.

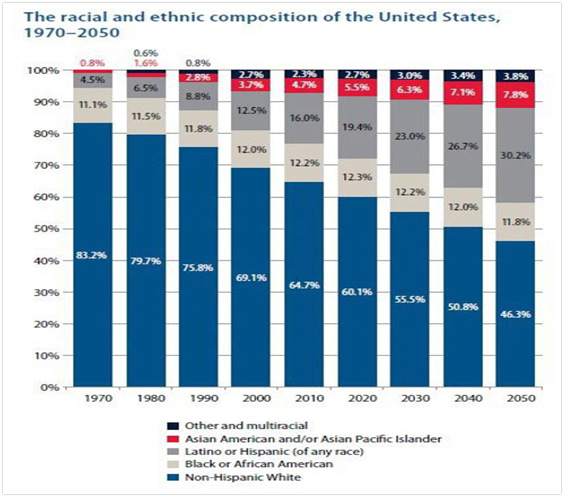

Beginning in the late 1970s, however, the rationale for affirmative action began to evolve. Driven by the rapid demographic change arising from the 1965 Immigration Reform Act, affirmative action could no longer be framed as a remedial action required to make up for past or present discrimination. Indeed, recent immigrants could not claim to be the victims of past discrimination in the United States nor claim to be the descendants of such victims. As a result, affirmative action’s justification shifted to the idea that the country’s institutions needed to “represent” the country’s racial and ethnic diversity. Importantly, affirmative action as “representation” could proceed in the total absence of benefits for African Americans (e.g. if they were already sufficiently or over-represented in an institution, they may not benefit from that institution’s system of preferential treatment).

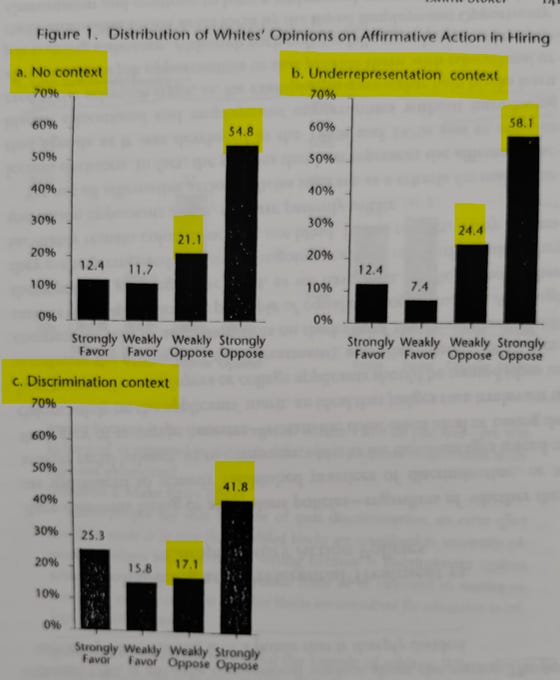

Once this shift from “reparational” to “representational” affirmative action happened, public support for the programs cratered. Survey experiments from 1998, for example, found that the American public was far more opposed to affirmative action as a means of increasing representation (82%) than there were to affirmative action as means of making up for past discrimination (59%):

At this point, it was clear that the idea that racial and ethnic diversity should be “represented” was an insufficiently compelling normative argument for most people. In order to provide an alternative foundation for “representational” affirmative action, the policy’s advocates began attempting to construct an empirical case for diversity. The idea here was to show that racial and ethnic diversity was not just a moral imperative but also a business and educational imperative. Businesses and universities that did not diversify would miss out on a range of benefits available only to those who did. The rationale for affirmative action, in other words, would be relocated from the realm of morality and ideology to the realm of science and pragmatism.

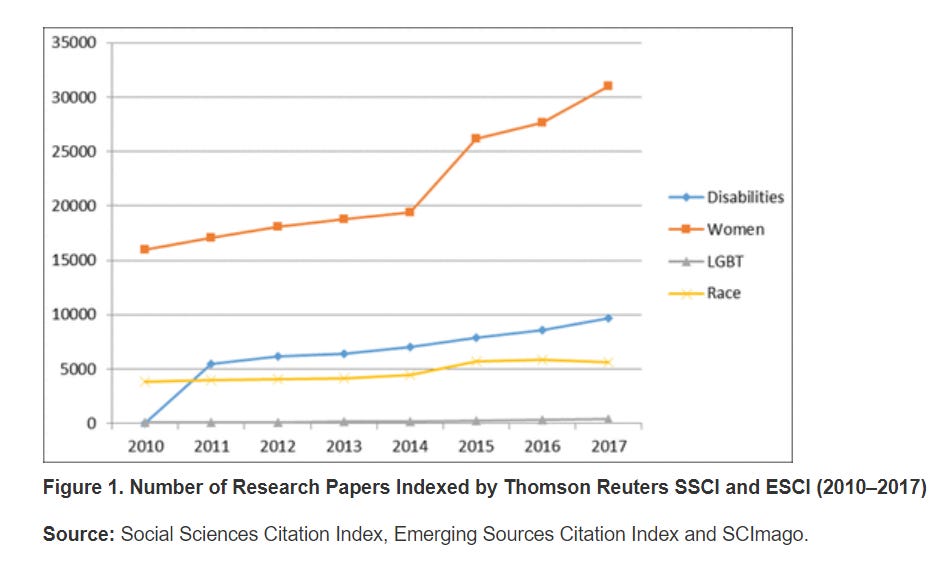

The institutional demand for research demonstrating diversity’s benefits has produced literally thousands of studies published on diversity EVERY YEAR. One article, for example, found that there were more than 45,000 papers on gender, racial, and disability diversity within the field of management in 2017 alone (see the figure below).

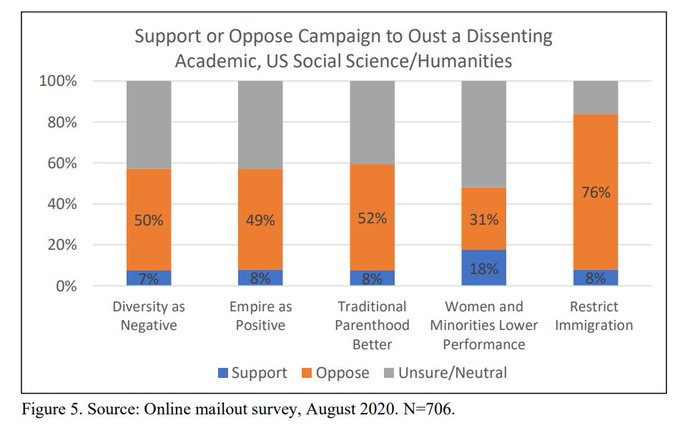

As I have pointed out previously, these studies are likely to dramatically overstate the benefits of diversity while minimizing its costs because of the rigidly enforced ideological monoculture within academia. Indeed, as Eric Kaufmann’s survey of faculty members shows, only half of professors in the social sciences and humanities would oppose a campaign to fire an academic who argues that “diversity is a negative.” Questioning the value of diversity (even if this questioning is motivated by a good faith interpretation of empirical data) has become disqualifying for faculty positions at contemporary American universities.

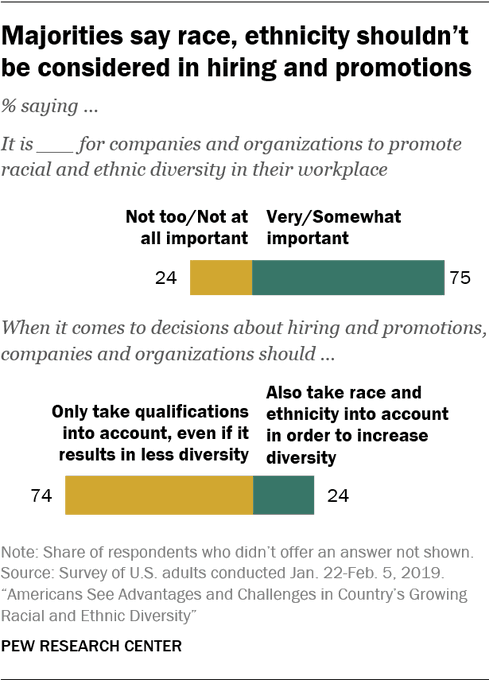

It is in this context, that we get the Supreme Court’s reconsideration of affirmative action and the social science-heavy brief authored by the tech companies. Currently, the idea that race should be a factor in who is accepted to a university (and who is not) is very unpopular. In March 2022, for example, Pew found that 74% of Americans said race “should not be a factor” in college admissions decisions (only 7% thought it should be a “major factor.”).

Similarly, a 2022 survey by Grinnel University found that 68% of Americans oppose universities “taking race into account in admissions decisions.” More importantly, the survey found no differences in support between whites and non-whites.

Blue Rose Research conducts surveys in which respondents are presented with the Democratic argument in favor of a given policy and the Republican argument. They can then pick which argument they find most persuasive. Using this method across 113 different issues, Blue Rose found that affirmative action is one of the least popular Democratic Party policy positions (only outpolling “lowering the voting age to 16”).

The public feels similarly skeptical about affirmative action in the workplace. While most value workplace diversity, very few want their employers to consider race when making decisions about hiring & promotion. According to the most recent Pew data, 74% want decisions about hiring and promotions to rely solely on “qualifications” “even if it results in less diversity.”

Perhaps most importantly, affirmative action has been voted down nearly every time it has appeared on the ballot. According to Richard Hanania, affirmative action has been voted on at the state level nine separate times between 1996 and 2020. It has been rejected 8 of those times (including, most recently, in 2020 in California):

All of this is just to say that the corporations are using their brief to promote a deeply unpopular policy. Their argument avoids presenting moral and ideological justifications for affirmative action and, instead, builds on decades of research designed to make a pragmatic and empirical case for allowing universities to discriminate on the basis of race.

This kind of argument, however, is only as strong as the academic research it cites. As I will show below, the business case for diversity is poorly supported by the research cited in the amicus brief and, more importantly, the evidence offered by Amici cannot be used to convincingly argue for the necessity of affirmative action in university admissions. Despite decades of research attempting to demonstrate otherwise, there’s no good evidence for allowing universities to discriminate on the basis of race.

How Much and What Kind of Diversity is Needed?

I’m going to focus my analysis of the tech company’s amicus brief on “Argument I - Racial and Ethnic Diversity Enhances Business Performance.” More precisely, I will discuss the studies presented in “Part A: Diverse Teams Make Better Decisions.” The authors of the brief begin this section in the following way:

this brief explains a wide variety of research-backed, tangible ways in which racial and ethnic diversity improves business. Empirical studies confirm that diverse groups make better decisions thanks to increased creativity, sharing of ideas, and accuracy. And diverse groups can better understand and serve the increasingly diverse population that uses their products and services. These benefits are not simply intangible; they translate into businesses’ bottom lines. For these reasons, it is no surprise that companies are investing substantially in diversity initiatives—a concrete acknowledgment of the value of a racially diverse workforce and leadership structure to business success.

In other words, the goal of this section is to provide “research-backed” evidence for the claim that diverse workforces produce benefits for employers.

Before evaluating the research presented in the brief it is worth asking why the diversity of an employer’s workforce is relevant to whether universities consider race and ethnicity when admitting students. According to the brief’s authors, the only way companies can recruit the kind of diverse workforce that would produce the previously mentioned benefits is if universities are sufficiently diverse themselves. As the brief states, “the “future of American business depends on universities’ ability to select racially and ethnically diverse student bodies.” Underneath this claim is an assumption about university admissions in the absence of racial preference; namely, that there will not be enough racial and ethnic diversity for businesses to hire a diverse workforce unless universities demonstrate a large preference based on an applicant’s race.

Is there any evidence that companies would struggle to recruit a workforce that is diverse enough to produce the workplace benefits they claim to seek? Answering this question requires specifying exactly how much and what kind of diversity is needed to generate positive business outcomes (e.g. to “make better decisions”). For example, does a team composed of whites, African Americans, and Asian Americans but no Hispanics produce the same amount, fewer, or more benefits than a team composed of whites and African Americans alone? Similarly, does a team that is perfectly representative of the American public in its racial composition (i.e. 65% white, 12% African American, 17% Hispanic, and 5% Asian American) perform better, worse or the same as a team that is majority-minority (e.g. 40% white, 60% non-white)? Without knowing what quantity and quality of diversity is minimal (never mind optimal) for producing “better decisions,” we can’t assess whether the companies even have a problem to be solved through more workplace racial diversity in the first place.

How Many College Graduates Do Amici Need?

A useful place to start in thinking through this issue is to identify how many college graduates Amici need to hire each year. The largest tech companies to sign on to the brief are Apple, Google, Meta, and HP. They employ 147,000 people, 135,301 people, 71,970 and 53,000 people, respectively. Since 2017, Apple has hired approximately 7,000 new employees a year, Google has hired approximately 20,000 new employees a year, Meta has hired approximately 13,000 new employees each year and HP, Inc. has hired an average of 0 new employees each year since 2017:

Collectively, then, the four largest tech companies in the country need approximately 40,000 new employees a year. Assuming that all of these positions require a college degree, will universities produce enough African American and Latino college graduates (who are the focus of Amici’s attention in the brief) to fill these needs if affirmative action is ruled unconstitutional?

How Many African American and Latino College Graduates Will There Be in the Absence of Affirmative Action?

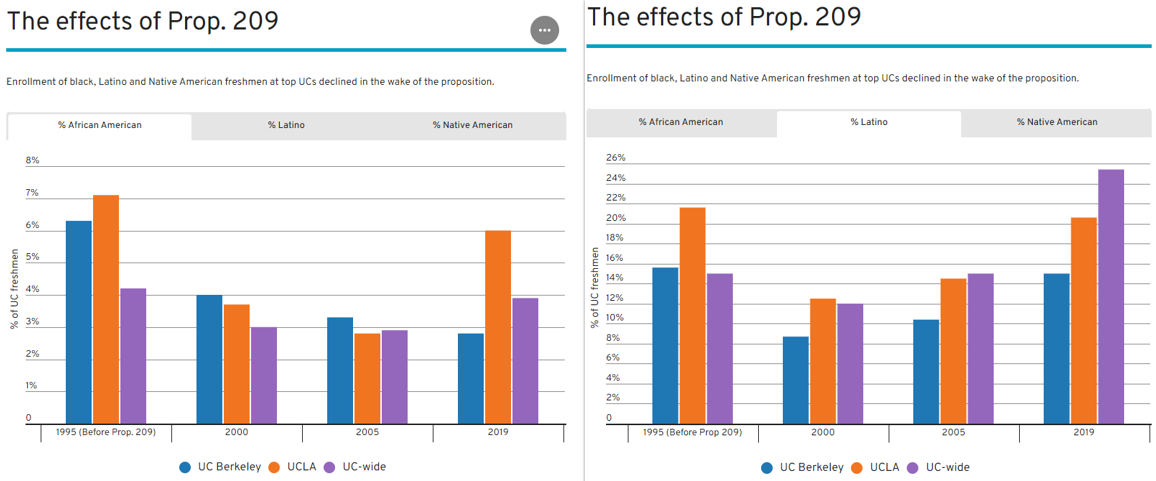

Assessing the exact impact of ending affirmative action on enrollment and, more importantly, graduation rates across racial groups is difficult. Data from the state of California (which repealed affirmative action in 1996 with the passage of Proposition 209) suggests that drops in enrollment might be initially large but rebound somewhat over time. As the data below show, African American and Latino enrollment in the UC system declined in the immediate aftermath of Proposition 209 but increased slightly in recent years.

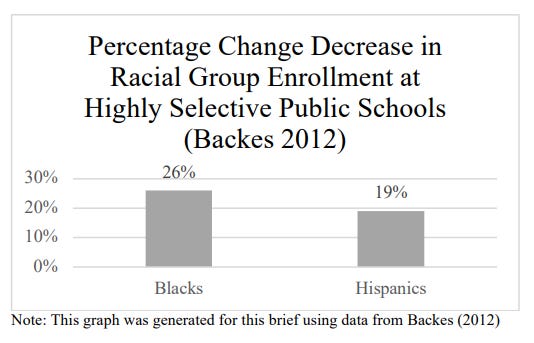

The most severe estimate suggests that African American enrollment would decline by 25% and Latino enrollment would decline by 19% in the absence of affirmative action:

Using this extreme estimate, how would the total number of African American and Latino graduates each year change if affirmative action stopped? In 2020, there were 532,720 Hispanic and 452,760 African American college graduates. If we assume there will be no improvement over time in African American and Latino enrollment after the end of race-based affirmative action (which is a highly questionable assumption), we would expect to have 10,121 fewer Hispanic and 11,717 fewer African American college graduates each year. Put another way, even with the end of affirmative action there would be nearly a million Hispanic and African American college graduates each year.

So, Will There Be Enough “Diversity”?

Even if the tech companies wanted to hire only African Americans and Latinos every year (to the complete exclusion of whites and Asian Americans), it seems they could easily meet their yearly hiring needs of 40,000 employees with the approximately 1 million new college graduates a year. If they wanted to adopt a slightly different standard for overall hiring, however, the task of hiring African Americans and Latinos would become even easier. Representing the national-level demographic composition, for example, would require hiring only 12,000 African American and Latino college graduates from the pool of nearly 1 million (1.2%). In short, with or without affirmative action, it seems that tech companies should have the labor supply they need to increase racial diversity in their workforces.

While it might be objected that the end of affirmative action would only hurt enrollment at “elite” or “select” universities and these are precisely the kinds of students Amici are attempting to recruit, raising this objection just begs the question of why Amici cannot adjust their standards for hiring if they see diversity as providing such value. Indeed, all of the arguments presented in Amici’s brief are about the importance of racial diversity alone (not about the importance of having diversity from the subset of students who attended elite universities). Corporations could hire without regard to education entirely and still accrue the benefits of diversity if they truly believed the research cited in the brief.

It is essential to point out here that private companies are already much freer to pursue affirmative action policies than universities under current federal law. In United Steelworkers v. Weber (1979), the Supreme Court ruled that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act “did not foreclose private race-conscious affirmative action plans.” This ruling gave the private sector far more flexibility than the government and academia in designing affirmative action programs. So, the question becomes: why can’t Amici use their own affirmative action programs to address diversity deficiencies rather than arguing for the government to implement a deeply unpopular policy? The solution to the problem of diversity in Amici’s workforce, in other words, might just be to have Amici lower their standards.

None of this answers the question, however, of exactly how much and what kind of diversity these companies are seeking to achieve. Throughout the brief, Amici argue for more racial diversity than they currently have in their workforces. For example, the authors of the brief write, “increasing racial and ethnic diversity throughout Amici’s workforces is the right thing to do.”

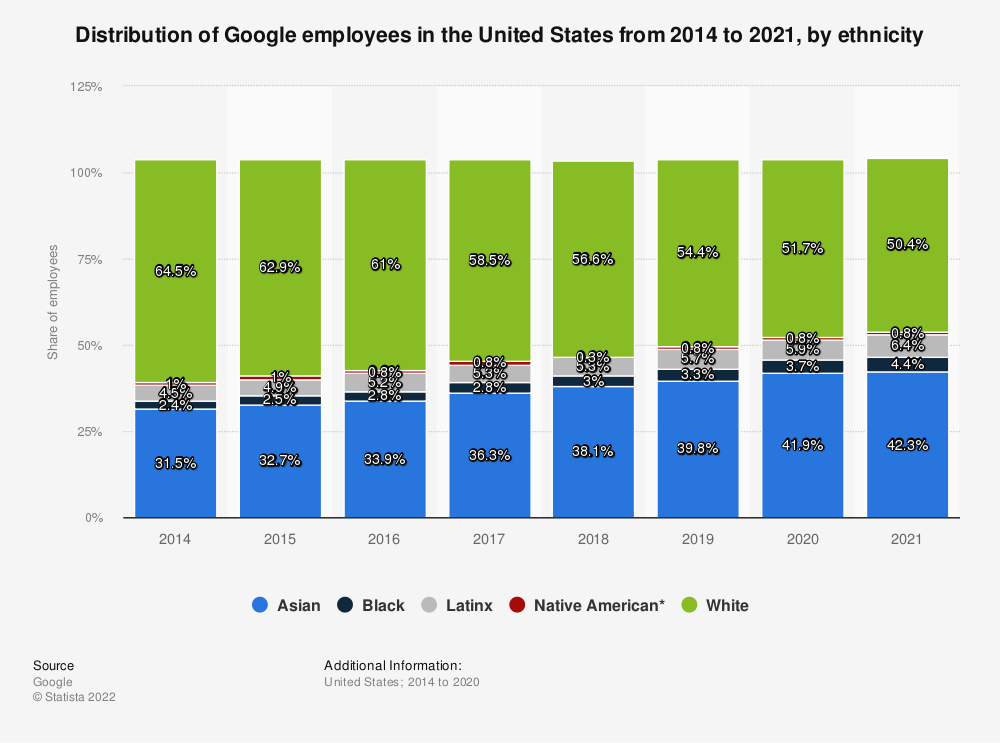

The idea that diversity needs to be increased (rather than simply maintained) raises the question of how diverse the companies are right now. To help answer this question, I tracked down data about the demographics of Google’s workforce:

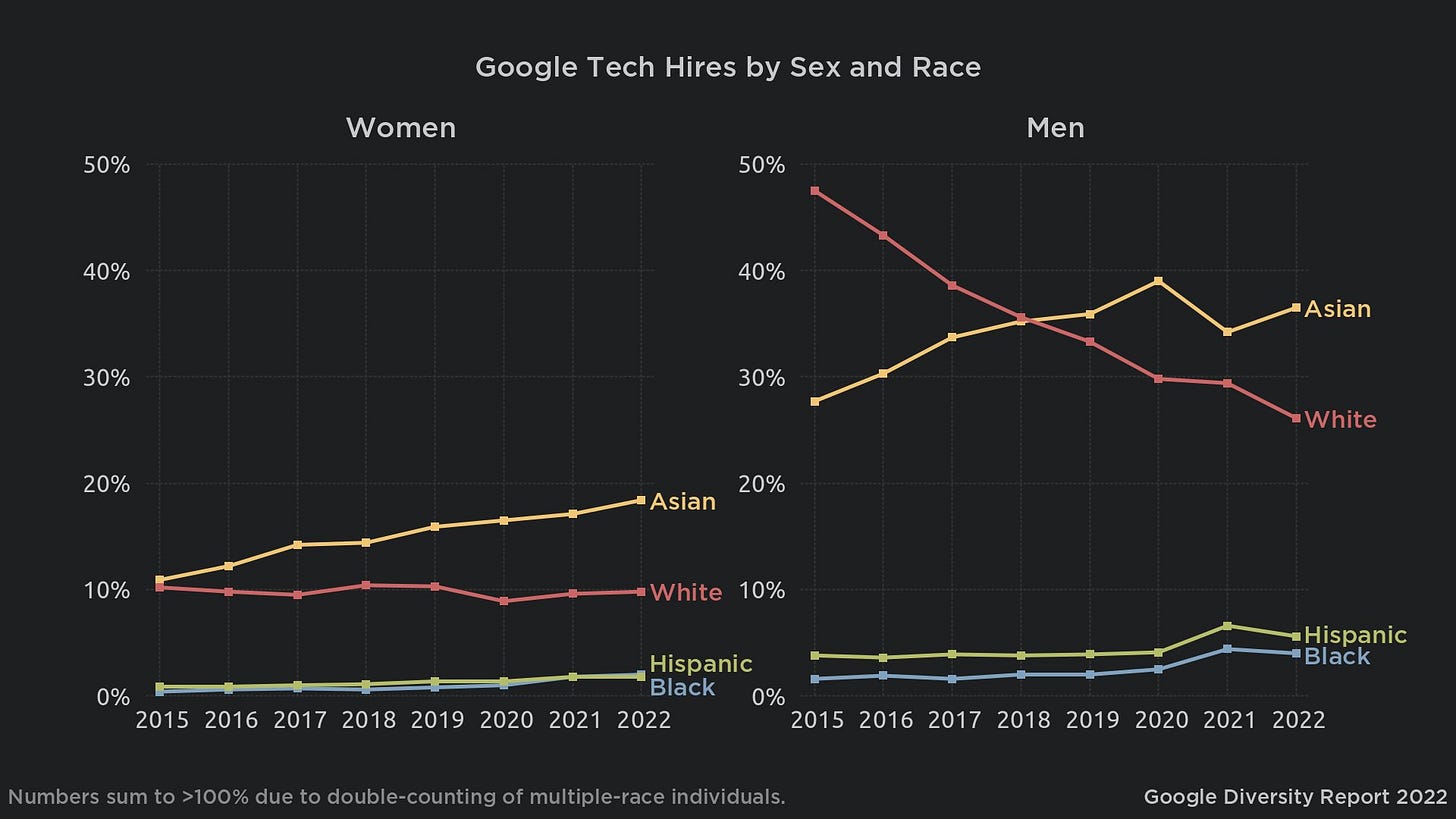

As the graph shows, Google’s workforce had a significant amount of racial diversity in 2021. As the graph also shows, the composition of Google’s workforce has changed quickly in recent years. Between 2014 and 2021, the percentage of Google employees who are Asian American increased by more than 10% and the percentage of African Americans more than doubled. Hiring data from Google's 2022 "Diversity Annual Report" suggests these trends will continue to accelerate. According to the report, Google “achieved our best year yet for hiring from underrepresented communities” by increasing the percentage of hires going to individuals from the “Black+,” “Latinx+,” and “Native American+” communities. These increases have led to a significant decline in the percentage of “White+” employees at Google but have not led to a decline in “Asian American+” employees:

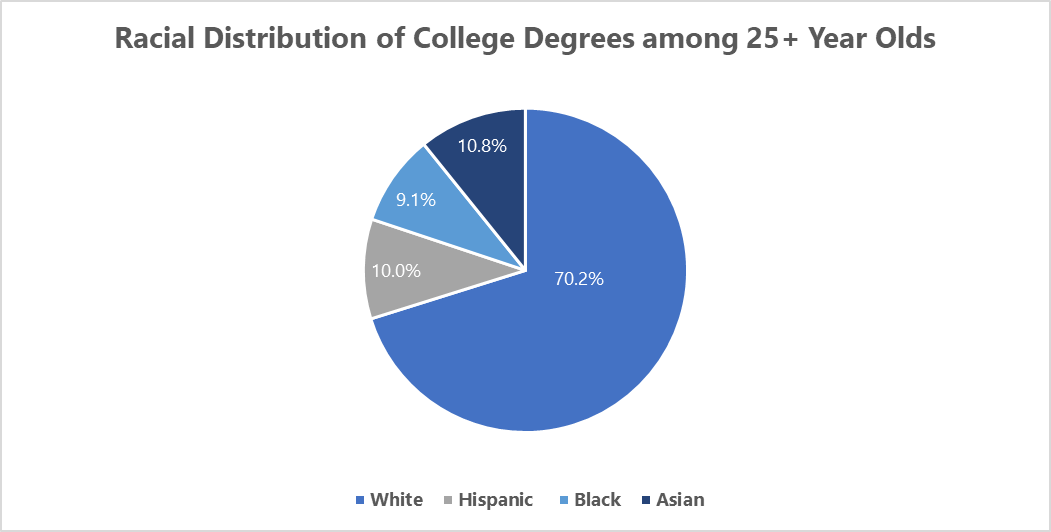

Google’s reference to “underrepresented communities” suggests they are evaluating their company’s diversity by comparing it to the country’s overall racial composition (i.e. 65% white, 12% African American, 17% Hispanic, and 5% Asian American). Given that the overwhelming majority of positions at Google select for a college education, a more appropriate baseline for comparison would probably be the racial composition of college graduates (see the graph of college degree holders over 25 years old below):

Regardless of the comparison (overall population or college graduates), it is clear that the company’s workforce vastly overrepresents Asian Americans (42.3% of current employees and 46.3% of new hires but only 5% of the population and 10.8% of college graduates). It is also clear that Google’s workforce only slightly underrepresents African Americans (5.3% of current employees and 9.4% of new hires while constituting 12% of the population and 9.1% of college graduates) and Hispanics (6.9% of current employees and 9.0% of new hires while constituting 17% of the population and 10% of college graduates). The most significant source of underrepresentation is among whites (who make up more than 60% of the population and hold 70% of the college degrees but account for only 48% of Google’s workforce and only 40.2% of their new hires).

Generally speaking, Google and the other companies who signed on to the brief are free to evaluate their employee’s racial composition against any standard they like. In the context of this section’s discussion of affirmative action, however, Amici is signing on to a very specific claim about racial diversity; namely, that they require more African American and Hispanic employees in order to perform better as companies (in the brief’s language, they need to “increase racial diversity” because “diverse groups make better decisions thanks to increased creativity, sharing of ideas, and accuracy”).

If it is to make a compelling case for affirmative action, then, the brief needs to present evidence that: (1) companies with more than the current level of African American and Hispanic representation (e.g. Google’s 5% of employees who are African American and 6% that are Hispanic) and less than the current level of white and Asian American representation (e.g. Google’s 50% of employees who are white and 42% who are Asian American) perform better than companies with different demographic racial compositions; and (2) the only way to achieve a workforce with this racial composition is by allowing universities to discriminate against applicants on the basis of their race.

To make a long story short, the brief does not do either of these things. More specifically, it fails to show any evidence at all that companies will benefit from moving beyond their current racial composition and it fails to demonstrate that affirmative action is a necessary path to achieving workforce diversity (independent of its benefits). Here, I will demonstrate this by reviewing four of the seven peer-reviewed studies the brief cites in support of its claim that “empirical studies confirm that diverse groups make better decisions thanks to increased creativity, sharing of ideas, and accuracy.” As I show below, each one of these studies has a set of problems that make it impossible for Amici to use them as part of an argument in favor of affirmative action in university admissions.

Study #1: “Do Pro-Diversity Policies Improve Corporate Innovation?”

Problem: The Study’s Measure of Diversity Conflates Race and Gender

The first cited study is Mayer et al.’s (2018) article “Do Pro-Diversity Policies Improve Corporate Innovation?” I will allow the authors of the brief to summarize this research in their own words:

“researchers found that companies with “a range of policies and characteristics” that indicate strength in diversity (including racial, ethnic, ability, and LGBT+ diversity) were positively associated with the “number of new product announcements per R&D dollar spent by a firm…..Companies with pro-diversity policies are more innovative.”

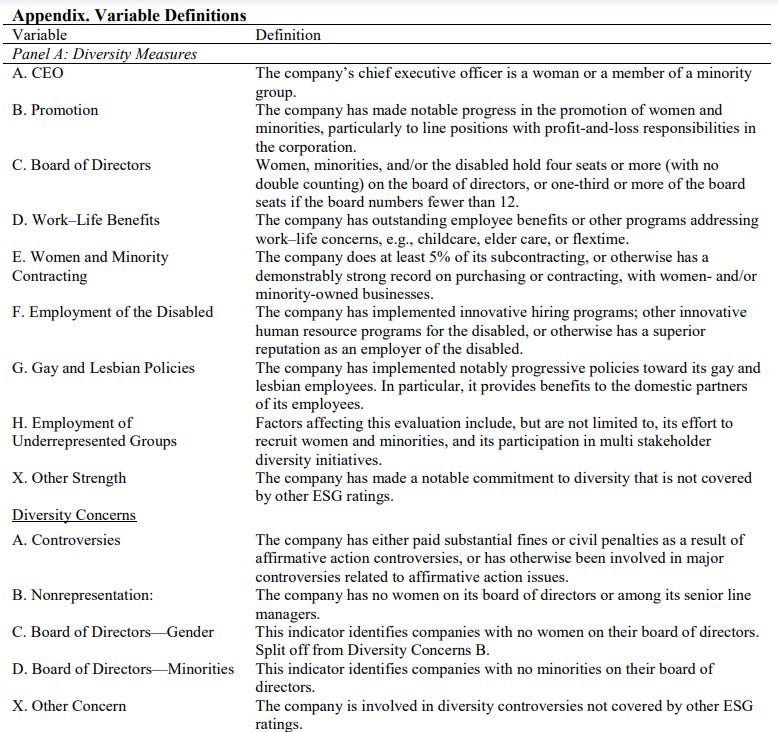

In order to measure the extent to which a company has “pro-diversity” policies, Mayer et al. use the MSCI’s Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) data. Mayer et al. do not use every variable contained in the MSCI ESG data. Instead, they choose the subset of variables related to gender, racial, and sexual orientation diversity (i.e. those classified as “Diversity Strengths” and “Diversity Concerns” by MSCI). To be exact, they rely on the following measures:

In the MSCI ESG data, “each firm is assigned a score of 0 or 1 for each strength or concern based on whether the firm meets the screen criteria.” Mayer et al. “calculate the net strengths of diversity as the difference between Diversity strengths and Diversity concerns (DIV = Diversity strengths – Diversity concerns).” Larger numbers on this measure indicate that a firm has more “pro-diversity” policies. Using this measure, Mayer et al. conclude that “pro-diversity policies are positively related to the number of new product announcements per R&D dollar spent by a firm.”

Does this study provide evidence that companies with more racial diversity perform better than companies with less racial diversity? No. The primary problem is that Mayer et al'.’s measure of diversity is that many of the items draw no distinction between race and gender. Consider the first “diversity” measure: “The company’s chief executive officer is a woman or a member of a minority group.” Bracketing the question of what constitutes being a member of a “minority group” under this measure, we have no way of determining whether all of the diversity included here is merely an artifact of companies hiring white women (not members of a “minority group”). The same problem applies to “Diversity Strength” measures B (“Promotion”), C (“Board of Directors”), E (“Women and Minority Contracting”), and H (“Employment of Underrepresented Groups”). Two measures under the rubric of “Diversity Concerns” even explicitly focus on the representation of women to the exclusion of members of “minority groups” (B and C).

In a nutshell, the problem with lumping race and gender together in this way is that it becomes impossible to determine whether the relationship between “pro-diversity” policies and firm performance is driven by racial representation alone, gender representation alone, or a combination of both. It is possible, for example, that gender representation is driving all of the pro-business effects that Mayer et al. describe as relating to “pro-diversity” policies more broadly. Representation for members of “minority groups” might have no effect or negative effects on business performance. We just can’t say given the measures used by Mayer et al.

Remember, Amici are attempting to argue for the necessity of affirmative action in university admissions by showing evidence that their businesses will benefit from increasing levels of racial diversity among their employees (e.g. this section of the brief is entitled “Racial and Ethnic Diversity Enhances Business Performance”). More directly, they are trying to make the case that increasing the percentage of African American and Hispanic employees above the current levels found in their companies will lead to “increased creativity, sharing of ideas, and accuracy.” Mayer et al.’s inability to distinguish between the effects of “diversity through female representation” and the effects of “diversity through racial representation,” however, means that we can’t conclude more racial diversity will lead to higher levels of performance. In other words, Mayer et al. fails to demonstrate that there is a business need for affirmative action.

There is another problems with using Mayer et al.’s measure of “pro-diversity” policies to make the case that companies need more diversity in their workforce overall; namely, that none of the 14 items in the overall measure is about overall workforce diversity. As the table above shows, the ESG data track racial and gender diversity for CEOs (Item A), Boards of Directors (Item C) and contracted firms (Item E) but not for the workforce overall. The measure of “Promotion” (Item B) can be scored as “pro-diversity” if a company “has made notable progress in the promotion of women or minorities” regardless of whether the levels of diversity are high or low among the workforce broadly. Even the measure labeled “Employment of Underrepresented Groups” does not tell us anything about the workforce diversity of a company (it only tells us about whether a company “makes efforts to recruit women and minorities”). In other words, the cited study fails (once again) to provide the evidence Amici needs it to provide in order to make a compelling business case for increased racial diversity.

Problem: The Study Measures Diversity as a Feature of HR Policy, not as a Feature of the Workforce

One last point deserves mention here: even if we believe that the “racial plus gender” diversity combination measure indicates a business benefit for racial diversity alone, Mayer et al.’s findings can’t help Amici make a convincing argument that the only way to achieve a workforce with more African American and Hispanic employees is by allowing universities to discriminate against applicants on the basis of their race. In fact, Mayer et al.’s research suggests that company policies, not the diversity of the broader applicant pool a company draws from, are the driving force in producing business benefits. Put differently, rather than arguing for the necessity of affirmative action, Mayer et al.’s work actually suggests that affirmative action is not needed at all.

Let me explain. If a business believed the results obtained in Mayer et al., they would want to advance their interests by adopting more “pro-diversity” policies. This would mean they should attempt to promote women and racial minorities currently working in the company (Items A and B), provide more “work-life benefits” to their employees (Item D), contract at least 5% of their business to women or minority-owned businesses (Item E), provide domestic partner benefits (Item G) and make an “effort” to recruit women and minorities (Item H). These adjustments would boost their “pro-diversity policy score” and, presumably, boost their performance.

Notice that all of these things are completely within a company’s control and require no changes to the eligible pool of potential applicants graduating from America’s universities. If Google wanted to, for example, they could make all of these changes tomorrow without ever needing to consider how universities accept or reject people. If universities were to end affirmative action or expand it, nothing would change from the perspective of companies attempting to follow Mayer et al.’s findings. In short, the brief’s reference to Mayer et al. actually undermines their claim that businesses can only accrue diversity benefits by allowing universities to discriminate on the basis of race.

Study #2: “Ethnic Diversity and Creativity in Small Groups”

Problem: The Study Compares “Equal Representation” Groups to “All-White” Groups

Next, the brief discusses McLeod et al.’s (1996) “Ethnic Diversity and Creativity in Small Groups” as evidence that diversity improves a company’s “creativity and innovation.” I’ll let the brief’s authors frame this study in their own words first:

“Another study illustrating this principle [how racial diversity improves creativity and innovation] asked small groups to brainstorm ideas to draw more tourists to the United States, and groups with the highest levels of racial diversity generated ideas that judges deemed “significantly more feasible . . . and more effective . . . than the ideas produced by the homogenous groups.”

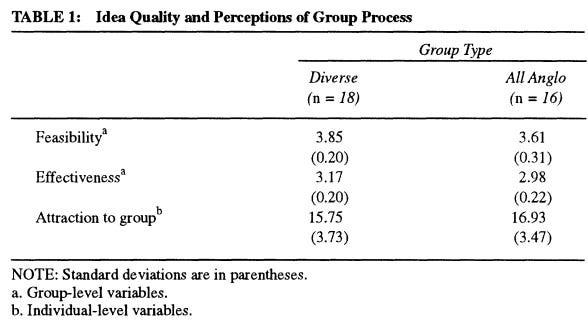

Let’s examine whether McLeod et al.’s research really shows that diversity improves creativity and innovation. The study included 135 students (94 men and 41 women) from “a large midwestern university.” From this group, the researchers created 18 “ethnically diverse groups” (which included one white, one African American, one Hispanic, and one Asian American participant) and 16 “all-Anglo groups.” The groups were asked to “spend 15 minutes generating as many ideas as possible to get more tourists to visit the United States.” Each idea was then graded on a five-point scale by two judges “in the travel industry” for their effectiveness and feasibility. In addition, the researchers assessed how “attracted” each subject was to their group (measured through items such as “Group members seem to like each other”). The results are shown in the table below:

As even this short discussion suggests, the brief’s summary is misleading. The study did not attempt to assess whether “groups with the highest levels of racial diversity” would generate better ideas. Groups were either “diverse” (i.e. had one member of each racial group) or “all Anglo.” As such, the study cannot speak to the relationship between levels of diversity in a group and its performance. We cannot know, for example, whether a group that was racially representative of the population (i.e. 68% white, 12% African American, 16% Hispanic, and 5% Asian American) would produce superior work to an all-white, African American, or Hispanic group. More importantly, the study only tells us about the performance of groups that are completely equal in their racial composition relative to groups that are completely racially homogenous.

This caveat is essential for thinking about the applicability of this study to real-world workplace environments. As shown above, the tech companies are already racially diverse (i.e. not “all-Anglo”). As such, we cannot know whether more diversity in their workforces (e.g. moving from 6% African American to 12% African American or moving from 5% Hispanic to 16% Hispanic) would have any effect on their employee’s creativity and innovation. Any increase in diversity would have to be assessed for its impact on creativity and innovation relative to a workforce that is already quite diverse (see above). Indeed, even if companies somehow engineered their workforces to match the racial parity examined in McLeod et al. (an impossible task given the current demographics in the United States), the odds that this small increase in diversity would produce a measurable difference in creativity and innovation are nearly zero. In short, McLeod et al.’s study does not actually advance Amici’s claims about the necessity of diversity and does not, therefore, bolster Amici’s argument that universities should use affirmative action in their admissions processes.

I should point out here that McLeod et al. are actually quite explicit about the inability of their study to address these issues. As they clearly explain in the paper, a major limitation of their choice to include equal numbers of whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans in each “diverse” group is that they cannot identify “how much diversity is enough to achieve measurable differences in performance.” What they do claim, however, is that:

“the work on the influence of minority opinion would suggest that even small numbers of people whos opinions are radically different from the majority’s can stimulate creativity.”

Put another way, to the extent that McLeod et al. make any recommendations about the amount of diversity needed to produce creativity and innovation benefits, it is very likely that Amici has already exceeded it. There is no evidence in this paper, therefore, that affirmative action in university admissions is needed to help these companies.

Problem: The Study Emphasizes Diversity’s Costs as Well as Its Benefits

According to McLeod et al.’s study, the observed benefits for diversity are vanishingly small and come with non-trivial costs. As the table above shows, the “diverse” group outperformed the “all-Anglo” group on effectiveness and feasibility by a mere .2 points each on a five-point scale. What’s more, the benefits were likely a function of unique features of the experimental context. As the authors explain, this experiment did not require the kind of conflictual negotiations typically found in workplace contexts requiring a single solution to a problem because it “required the subjects to simply accept all the solutions offered by other group members.” The benefits of diversity, in other words, may never appear in the real-world workplaces Amici operates.

More importantly, these small and context-specific benefits came with a cost. As McLeod et al. explain:

“members of heterogenous groups may have had more negative affective reactions to their groups than did members of homogenous groups…..The results of this and other studies have suggested that increased heterogeneity may also be related to negative affect, communication difficulties and turnover.”

In other words, the relatively small benefits in work production came at the relatively large expense of group cohesion and satisfaction. Contrary to Amici’s claim, therefore, this study doesn’t actually provide clear evidence that diversity helps business. The net impact is more mixed. If diversity is not necessarily great for business, there is no strong rationale for affirmative action in university admissions.

Study #3: “Multicultural Experience Enhances Creativity: The When and How”

Problem: The Study Measures Diversity as a Feature of a Slideshow, not as a Feature of a Workforce

Next up in the brief is Leung et al.’s (2008) study on multicultural slideshows and Cinderella stories. As the brief’s authors write:

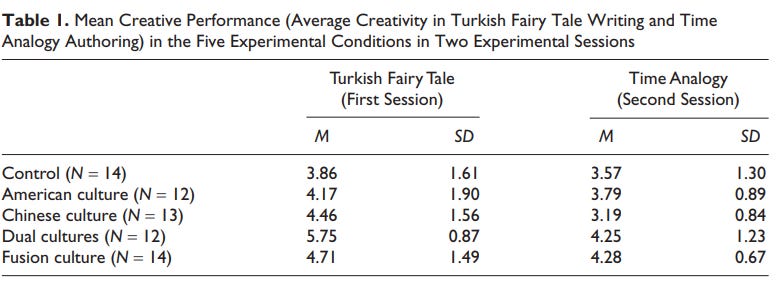

“One example [of how diversity produces creativity] is a study in which white undergraduate students watched a slideshow—either about Chinese culture, American culture, American and Chinese cultures in juxtaposition, or American-Chinese fusion culture—before writing a Cinderella story for Turkish children. Researchers found that those who had watched the slideshow juxtaposing American and Chinese cultures or the slideshow depicting American-Chinese fusion culture wrote more creative stories than other participants—providing “direct evidence for the causal role of exposure to a foreign culture in creative performance.”

Leung et al.’s study included 65 “European American undergraduates (29 females; mean age = 19.05 years) who “participated in two experimental sessions in exchange for course requirement credit.” There were between 12 and 14 students in each of the study’s five experimental conditions. The results (with creativity scored by “judges” on a seven-point scale) are shown below:

There are obvious concerns about external validity here - including the tiny and unrepresentative sample (65 white undergraduates at a single university), the bizarre task given to the experimental subjects (writing a version of the Cinderella story for a hypothetical group of Turkish children) and the highly individualized, non-competitive and inconsequential nature of the experimental context (writing the story alone with low stakes rather than working collectively on a high stakes project).

Independent of these concerns, the brief’s reference to this work is confusing given that it actually makes a strong argument against the need for racial diversity in the workforce. The causal variable in this study is the “slideshow” (producing changes in “creativity”). In other words, this study is about the efficacy of slideshows and says nothing about the business-related benefits of people from different racial or ethnic backgrounds working together. More importantly, if creativity can be increased among an all-white group simply by exposing them to a slideshow about multiple “cultures,” there is no need to hire based on diversity at all. Indeed, apparently with the right kind of multicultural, multimedia presentation, companies can boost creativity in a way that is (presumably) easier to implement than engineering their workforces to achieve a particular racial or ethnic composition.

Given that this study suggests that companies do not need any actual racial or ethnic diversity in their workforce, there is no need to allow universities to take race or ethnicity into account in their admissions process. Remember, the companies are arguing that universities need to employ affirmative action in order to produce the diverse workforce that helps the companies succeed. If companies do not actually need diversity to succeed, there are no grounds for allowing a divisive and illiberal program to continue.

Study #4: “Ethnic Diversity Deflates Price Bubbles”

Problem: The Study Emphasizes Diversity’s Costs as Well as Its Benefits (Again)

The brief then cites one of the most widely referenced studies in public-facing arguments about diversity: Levine et al.’s “Ethnic Diversity Deflates Price Bubbles.” Levine et al. conduct an experiment that compares fake stock trades in four ethnically homogenous “markets” of 24 college students in Kingsville, Texas and five ethnically “diverse markets” of 30 college students in Kingsville, Texas. According to the brief:

The study found that traders in ethnically homogenous markets were ‘significantly less accurate’ in making pricing decisions ‘and thus more likely to cause price bubbles.’ Traders in homogenous markets [were] more likely to accept offers that are above true value.

Falling into the same trap that they did in their discussion of McLeod et al.’s study, the authors of the brief never mention the potential costs of diversity. Their silence on diversity’s costs is particularly strange in the context of referencing Levine et al.’s work because Levine et al. are incredibly explicit about the potentially high costs of diversity. In fact, the entire theoretical justification for their work is that observable racial and ethnic diversity enhances skepticism, distrust, and competition. As they write:

"Ethnic diversity facilitates friction. This friction can increase conflict in some group settings, whether a work team, a community or a region. Conversely, ethnic homogeneity may induce confidence, or instrumental trust, in others' decisions (confidence not necessarily in their benevolence or morality, but in the reasonableness of their decisions, as captured in such everyday statements as “I trust his judgment”).

According to Levine et al., this “friction” can produce positive consequences in some contexts and incredibly damaging consequences in others. Specifically:

In modern markets, vigilant skepticism is beneficial; overreliance on others’ decisions is risky…Such friction, however, can cause conflict and complicate collective decisions. The challenge, then, is in establishing rules and institutions to address ethnic diversity and its effects. Without them, conflict can be destructive; with them, diversity can benefit the collective."

In other words, previous research indicates that racial and ethnic diversity might make things much worse in team and non-market settings (like the ones found in tech companies). If diversity has significant drawbacks, affirmative action becomes a less appealing policy option.

Problem: The Study Compares “All Hispanic” Groups to “Diverse” Groups

Levine et al.’s study “created homogeneous markets by including only participants that were Latinos.” In “diverse markets,” Levine et al. explain, “at least one participant was of a numerical minority ethnicity.” The “minority ethnicity” might have been African American, Asian American, or white. The authors, however, never say and they are never explicit about how many “minority ethnicity” members were included in their five “diverse” trading markets.

If we assume that each “diverse market” in Levine et al.’s experiment had only one “minority ethnicity” participant, the study may have had a total of 49 Hispanic and 5 non-Hispanic college students in their sample. It is even possible that the study did not include a single white, Asian American, or African American participant. Put differently, the study created a highly artificial situation in which a national demographic minority (Hispanics) constituted a huge experimental majority.

Obviously, Levine et al.’s findings cannot tell us anything about the amount or ratio of diversity required to begin accruing the “accuracy” benefits described in the brief. Although specific details of market composition are never described, it is possible that only one “minority” member was included in each of the “diverse” markets. Would accuracy in pricing assessments increase or decrease with more “diversity” (e.g. if two or three “minority” members were included in the market instead of one)? Would the presence of more than one kind of racial or ethnic diversity (e.g. one African American, one white, one Asian American instead of just one African American) lead to more or less accuracy in perceptions? The study does not say because the study cannot say. In other words, Levine et al. cannot advance Amici’s claim that they need to “increase” the amount of racial diversity in their workforces.

Problem: The Study Assess Diversity Among Strangers and not Among Teams

Participants in Levine et al.’s study were strangers. They were alerted to the racial and ethnic homogeneity or diversity of their market by being asked to sit in a waiting room for a few minutes with other study participants. As the study’s authors explain:

“While waiting, participants were allowed to speak with one another and had many opportunities to perceive others’ ethnicity, a categorization process that is typically automatic and highly accurate. Once six participants arrived, an experimenter assigned them to separate cubicles, each of which was equipped with a networked computer.

The study makes no attempt to distinguish the effects that diversity might exert on the decision-making of complete strangers who share nothing in common other than their ethnicity and the effects that diversity might exert on the decision-making of people who share some common, non-ethnic set of identities, experiences, or responsibilities. This distinction is important because, according to Levine et al., the benefits of diversity are a direct and exclusive consequence of the distrust that diversity produces among strangers. In their words:

“Ethnic diversity was valuable not necessarily because minority traders contributed unique information or skills, but their mere presence changed the tenor of decision making among all traders…Diversity facilitates friction. In markets, this friction can disrupt conformity, interrupt taken-for-granted routines, and prevent herding. The presence of more than one ethnicity fosters greater scrutiny and more deliberate thinking, which can lead to better outcomes.”

There is a considerable body of research suggesting that shared experiences, mutual dependence, and the formation of superordinate identities can reduce friction between members of distinct groups. My strong suspicion is that Amici invest considerable time, energy, and resources in team-building and training exercises designed to reduce friction between employees. Presumably, this reduced friction would also reduce the benefits of diversity indicated by the study. If diversity has fewer benefits than indicated by the study, the case for affirmative action in university admissions is considerably diminished.

Problem: The Study Looks at Diversity’s Effects in the Context of Individual Competition and not in the Context of Collective Cooperation

After having a chance to observe the racial and ethnic composition of the group, participants in Levine et al.’s experiment were isolated from each other. While “trading” during the experiment, “participants could not see each other or communicate directly.” The experimental context, in other words, was highly individualized and decisions about how to act were made alone and in the absence of any interpersonal communication.

What’s more Levine et al.’s experiment sets up zero-sum competition between its individual participants by creating a simulated stock market (i.e. an individual participant earns more money only by taking money from another participant in the form of relatively beneficial asset “trades”).

The authors of the brief ignore these crucial features of Levine et al.’s experimental design and, instead, include the results under the heading “Diverse Teams Make Better Decisions.” It should go without saying that group-based, cooperative information processing, and decision-making operate according to fundamentally different dynamics than individual, competitive information processing and decision-making.

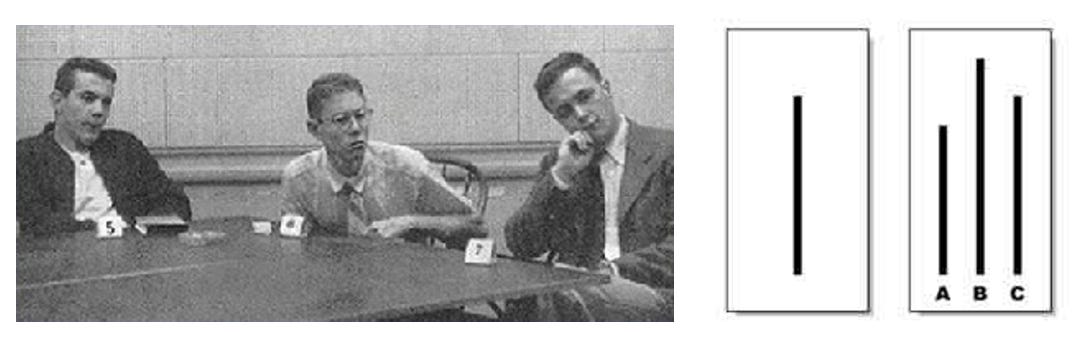

Consider Solomon Asch’s famous conformity experiments (pictured above). When left alone to determine which lines matched in length, experimental subjects reported the correct answer in more than 99% of cases. When asked to make the same identification in the context of a group giving incorrect answers, however, 37% of respondents gave an incorrect answer in order to conform to the rest of the group. Taking a finding about how individuals make decisions in artificially sequestered environments and claiming that it reveals something about how “teams” process information in a corporate environment is a stretch. Put differently, Levine et al.’s experiments cannot provide Amici with the evidence they need to make a strong argument in favor of university affirmative action.

Conclusion

I’ve focused here on the use of social science research to justify race-based affirmative action in university admissions. If the social science research was to successfully bolster Amici’s argument that “diverse groups make better decisions,” the unit of analysis in the cited studies (i.e. the entity about which we are making claims) should have been the “work team,” the causal variable should have been the “team’s racial and ethnic composition” and the outcome variable should have been “decision quality” (with attention to the costs and benefits resulting from diversity). Further, the study’s findings should have identified exactly how much and what kind of racial diversity is needed to produce the benefits Amici seeks. Finally, the cited research should have indicated that allowing affirmative action in university admissions is the only path to achieving these benefits. We should have expected, in other words, for the brief to discuss research that meets a very specific set of criteria.

As I describe above, however, this is not what the brief chooses to do. Instead, it offers up a number of studies about units of analysis (e.g. individuals, corporations), causal variables (e.g. watching movies, company-level diversity policies), and outcomes (e.g. innovation, benefits but not costs) that have nothing to do with the claim that “racially diverse teams make better decisions.” More importantly, the cited research does not suggest the quantity or quality of diversity needed or indicate that affirmative action is required to achieve more diversity. In fact, many of the studies suggest that the companies may already have sufficient levels of racial diversity. In other words, the brief cites studies that fail to make a compelling case for diversity’s business benefits. As a result, there is no compelling case for affirmative action in university admissions.

It’s important to point out here, however, that the weaknesses in the studies cited in this section of the brief (“Part A: Diverse Teams Make Better Decisions”) do not undermine arguments or evidence presented in other parts of the brief. Most importantly, it does not undermine the claim that universities need to be diverse because it educates people in a particular way. That claim, which is explained in the brief, needs to be examined separately.

This section’s title and substance owes a great deal to Jack Citrin’s 1996 piece “Affirmative Action in the People’s Court.”

Thanks for this well written and clear analysis. Another issue with claims about the benefits of diversity (or any other HR policy) for companies, is establishing the direction of causation. Even if the studies did show a clear and relevant correlation between increasing diversity and better company performance (which they don’t for the reasons in the essay) it could just as easily be the case that successful companies face more pressure to increase diversity than less prominent companies. And they can diversify without materially lowering standards due to being desirable workplaces with a deep pool of highly qualified applicants to choose from. I.e. that success leads to greater diversity rather than vice versa.