The Military’s White Democrat Problem

Conservatives have correctly identified whites and "wokeness" as key components of the military’s recruitment crisis. Unfortunately, they are focusing on the wrong whites and the wrong "wokeness."

An “Unprecedented” Recruitment Crisis

The U.S. military is facing an “unprecedented” recruitment crisis, with the Army, Navy, Air Force, Coast Guard, and National Guard all failing to meet their enlistment goals in 2022. This recruitment crisis is partly a function of the fact that so few young people are now able to serve in the military due to obesity, educational deficiencies, mental health problems, or criminal records. In fact, according to the Associated Press, “only 23% [of American youth] are physically, mentally, and morally qualified to serve without receiving some type of waiver.”

The recruitment crisis is not entirely a consequence of these metastasizing physical, mental, and moral problems, however. It is also a direct result of the growing unwillingness of young people to serve in the armed forces. The most recent estimates “show that only 9% [of America’s youth] are even interested in military service.”

So why are so few young people willing to serve in the military? For some conservative observers, the answer is obvious: the Pentagon’s increasingly “woke” diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies are alienating the groups most inclined to serve in the armed forces (white conservatives, white Southerners, and whites living in rural areas).

There’s no shortage of pieces advancing this kind of argument. Consider, for example, Jimmy Byrn’s recent article in the Wall Street Journal (entitled “What if They Gave a War and Everybody Was Woke? The military’s embrace of faddish politics may make activists happy, but it’s driving away recruits”). Byrn begins by reviewing data on the military’s recruitment crisis:

Nearly every branch has struggled to meet its recruitment goals for 2022, with some falling as short as 40%. Worse yet, only about a quarter of America’s youth meet current eligibility standards—and recent surveys show only 9% are even interested.

Byrn then walks through a laundry list of “woke” policies initiated during the first few months of the Biden administration:

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin mandated that every military unit conduct a “stand-down” to confront “extremism in the ranks.” The chief of naval operations, Adm. Mike Gilday, added Ibram X. Kendi’s “How to Be an Antiracist” to his reading list for sailors …The Navy has mandated gender-sensitivity training, and released a video encouraging sailors to closely police the use of pronouns as well as everyday language, declaring that those who fail to comply aren’t “allies” of their fellow sailors.

Byrn argues that these changes are a “repellent” for conservatives and Southerners:

“[S]uch measures have amounted to a form of antirecruitment for prospective enlistees. The Pentagon is appealing to activists at the expense of those most likely to serve. The military has historically drawn an outsize proportion of recruits from conservative Southern states….Unsurprisingly, military members privately skew conservative. In the 2018 midterm elections, nearly 45% of service members surveyed indicated they would back Republican candidates, versus 28% who favored Democrats. Support for Republicans among veterans was similarly strong in 2020.”

Striking a similar tone in Imprimis, Thomas Spoehr argues that:

“Wokeness in the military affects relations between the military and society at large. It acts as a disincentive for many young Americans in terms of enlistment…Recent reports show the military’s dismal failure to gain new recruits in adequate numbers...Is anyone surprised that potential recruits—many of whom come from rural or poor areas of the country—don’t want to spend their time being lectured about white privilege?”

Unlike Byrn, Spoehr sees “wokeness” in the military beginning prior to 2021. As he points out, “The push for it didn’t begin in the last two years under the Biden administration” and many of the military’s “woke” policies have been in place since at least 2015.

The JAMRS Surveys

Is there any evidence that the desire to serve in the military has declined among white Republicans, white Southerners, and white rural residents since 2015 as a result of “wokeness” within the military? The only easily accessible data on this question (i.e. data that an average citizen without advanced knowledge of statistical software packages can locate) comes from eight, short PowerPoint presentations based on the Department of Defense’s JAMRS surveys.

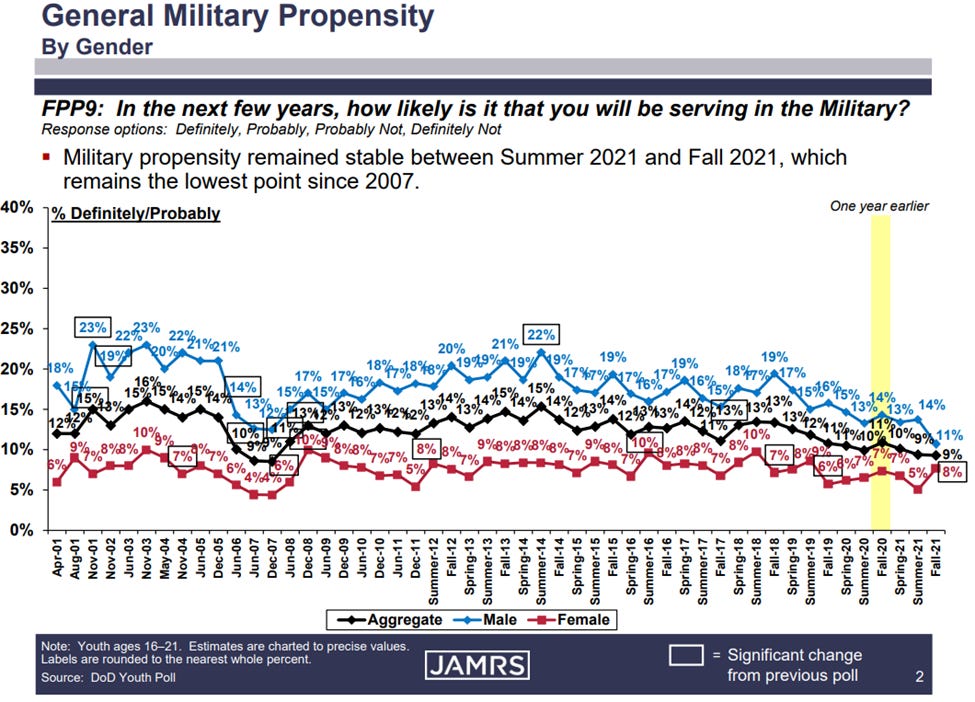

Three times a year, the JAMRS surveys gather a nationally representative sample of more than 3,000 16- to 24-year-olds in the United States. The survey asks its respondents, “How likely is it that you will be serving in the Military in the next few years? (Definitely, Probably, Probably not, Definitely not).” The aforementioned PowerPoint presentations display aggregate and subgroup (racial and gender) trendlines over time:

Figure #1 – Likelihood of Military Service (JAMRS)

As Figure #1 shows, the percentage of 16 to 21-year-olds saying they will “definitely” or “probably” serve in the military during the “next few years” averaged approximately 13% in 2015. After dropping somewhat between 2015 and 2016, the percentage stayed around 12% through 2019. In 2020, however, the aggregate likelihood of military service dropped to 10%. By 2021, the number reached a historic low of 9%.

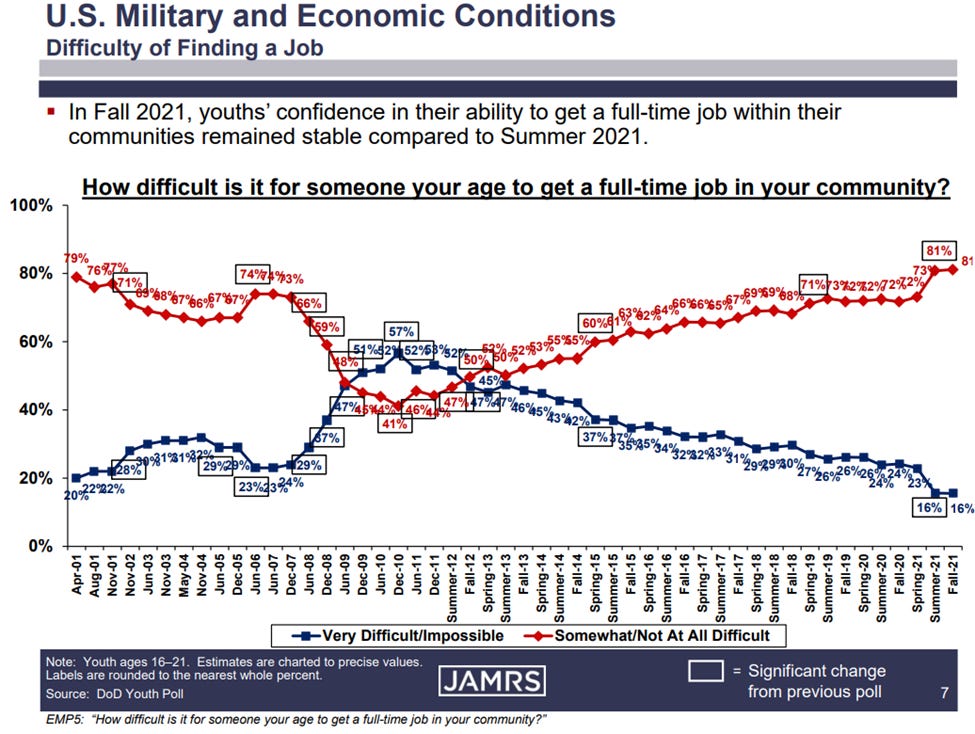

The JAMRS presentations imply that labor market competition, not “woke” DEI policies, is behind young people’s diminishing propensity to serve. Indeed, the survey data on likelihood is immediately followed in the JAMRS PowerPoint presentations by a section entitled “U.S. Military and Economic Conditions.” In this section, results from a question on job prospects (“How difficult is it for someone your age to get a full-time job in your community?”) are presented:

Figure #2 – Economic Perceptions (JAMRS)

These presentations send a clear message: the likelihood of serving in the military is declining because the difficulty of getting a “full-time job in your community” is also going down. In other words, the recruitment crisis has an economic cause and requires an economic solution.

Unsurprisingly, the publication of the most recent JAMRS PowerPoint slides (Fall 2021) was followed by a steady stream of calls for expanding military pay and benefits so that the armed forces might better compete with other career opportunities. Representative Anthony Brown, for example, issued a statement demanding the Pentagon provide “better pay, training, opportunities, connections, and benefits” as part of an effort to “do more” to encourage young Americans to join the military. Striking a similar tone, Representative Jason Crow told Politico that the Pentagon should “provide enlistment incentives and bonuses” to make military careers seem more desirable to young people than other job opportunities.

The most notable example of how the JAMRS data provoked calls for increased military benefits came with Brittany Dymond’s (the Associate Director of the National Legislative Service for the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States) congressional testimony on the “Status of Military Recruiting and Retention Efforts Across the Department of Defense.” In her statement, Dymond relied exclusively on the JAMRS reports to argue that “Congress must ensure military benefits such as pay, health care, tuition assistance, and retirement are competitive with the private sector, continuously improved, and come without cost increases to members and families as applicable.”

The runaway economic optimism illustrated in Figure #2 is undoubtedly an important factor in the military’s ongoing recruitment crisis and military pay, educational incentives, and benefits are essential for encouraging young people to enlist. What I want to explore here, however, is the idea (implied by the JAMRS presentations) that economic factors are the only drivers of the recruitment crisis. Specifically, I want to test Byrn and Spoehr’s claim that interest in serving in the armed forces is declining among white Republicans, white Southerners, and white rural residents as a result of the military’s growing “wokeness.”

Unfortunately, with the exception of what is contained in the eight short PowerPoint presentations posted on the JAMRS website, the JAMRS data is not publicly available. As a result, we do not know what other questions were asked in the JAMRS survey or how responses to those questions may have correlated with each other (including with the “likelihood of serving” question). Most importantly, we don’t know whether JAMRS asked questions about the desire to serve (as opposed to the mere likelihood of serving) or about political beliefs.

In this post, I’m going to take advantage of a largely unexamined dataset – the Monitoring the Future survey – to explore preferences for military service among whites since 2015. As I demonstrate, both the JAMRS reports and conservative observers are misdiagnosing the causes of the recruitment crisis. The JAMRS reports suggest the military is facing a short-term economic problem. As I will show, the military is actually facing a longer-term political problem. While conservative observers like Byrn and Spoehr correctly intuit the military’s political problem, they are mistakenly locating that problem among Republican, Southern, and rural whites. They are also mistakenly attributing that problem to the Pentagon’s “woke” DEI policies. In fact, the political problem exists almost exclusively among white Democrats and it is almost exclusively a function of this group’s increasingly negative attitudes toward the country and toward the military.

Misdiagnosing the causes of the recruitment crisis will mean policy interventions (e.g. higher pay and more generous benefits) to enhance enlistment will fail. Given the scale of the recruitment crisis already, this failure would be catastrophic. My goal here is to help avoid this catastrophe by drawing attention to the role that political “wokeness” is playing in killing military “willingness.” The military cannot successfully fight what is partly an ideological war with economic weapons alone.

The Monitoring the Future Data

Every year, the Monitoring the Future project collects a “large, distinct, nationally representative samples of 12th-grade students in the United States.” The survey asks over 100 questions to more than 10,000 American high school seniors in order to “explores changes in important values, behaviors, and lifestyle orientations of contemporary American youth.”

Most important for my purposes here, the Monitoring the Future survey asks respondents a question about their partisanship and two questions about their views on military service:

How likely is it that you will do each of the following things after high school… Serve in the armed forces? (Definitely Won’t, Probably Won’t, Probably Will, Definitely Will)

Suppose you could do just what you'd like and nothing stood in your way. How many of the following things would you WANT to do? (Mark all that apply.) Serve in the armed forces?

These two questions track distinct, yet closely related dimensions of young people’s orientation toward military service. The “likelihood of serving” question is nearly identical to the item asked in the JAMRS surveys. This question avoids making any reference to the respondent’s preferences about military service. Instead of asking what the respondent “wants” to do, it asks them only what it is “likely” that they will do (independent of their desires). As a result, the question primes respondents to balance their preferences against their opportunities and constraints. It is possible, for example, that a respondent might answer this question by selecting the “definitely will” response because he or she imagines a reinstatement of the military draft (forcing them to serve regardless of whether they want to or not). Alternatively, a respondent might have a lifelong dream to serve in the military but realize that it will not happen because of familial obligations that require them to stay close to home. In short, this question asks respondents for a measured prediction about their future, not for a decontextualized disclosure of their preferences.

By contrast, the question about “wanting” to serve in the military directly taps what young people feel about serving in the military. The question instructs respondents to ignore the opportunities and constraints they face when deciding what to do with their lives. Indeed, it begins with the sentence, “Suppose you could do just what you'd like and nothing stood in your way….”). The question also explicitly primes respondents to think about their desires. Specifically, it asks them, “How many of the following things would you WANT to do? [capitalization in original].”

Byrn and Spoehr’s claims are primarily about the desire of Republican, Southern, and rural whites to serve in the military rather than the likelihood that they will serve. I will focus my attention here, therefore, on this dimension of attitudes toward military service.

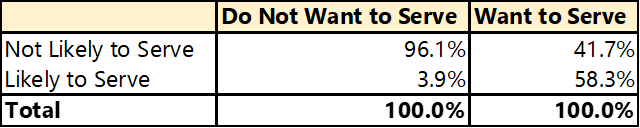

Relatedly, I should also point out that the MTF data underscores the problem with focusing on likelihood alone (as the JAMRS data apparently does). Empirically speaking, desire to serve in the military is not a sufficient condition for being likely to serve in the military. As Figure #3 shows, since 2015, only 58.3% of high school seniors who expressed a desire to serve also thought they would eventually enlist in the armed forces. Desire to serve in the military does seem, however, to function as a necessary condition for being likely to serve in the military. As Figure #3 shows, those who do not want to serve in the military stand almost no chance of saying that they will serve in the future. To be more precise, more than 96% of those who said they did not want to serve in the military also said that they “probably won’t” or “definitely won’t” serve in the military.

Figure #3 – The Relationship between Likelihood of and Desire for Military Service (MTF)

The fact that desire works as a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for being likely to serve in the military suggests that we need to pay particular attention to the size and growth of the “do not want to serve” category. If it becomes too large, there is very little the military can do (e.g. increase pay and benefits) to recruit the soldiers it needs. The JAMRS data, with its exclusive focus on the estimated likelihood of service, directs our attention away from this basic fact and necessarily leads us to focus entirely on economic solutions to recruitment problems. Any attempts to fully understand the military’s recruitment crisis should, therefore, use the MTF data (and, in particular, the desire to serve question). Surprisingly, however, I was unable to find even a single report, statement, or piece of congressional testimony related to military recruitment from the last 10 years that cited the MTF data.

Testing Byrn and Spoehr with the MTF

Byrn and Spoehr’s claims about “woke” DEI policies acting as a “repellent,” a form of “antirecruitment” and a “disincentive” for white Republicans, white Southerners, and rural whites are testable using the MTF data. Indeed, if the military’s increasing “wokeness” after 2015 (and particularly after Biden took office in early 2021) is driving individuals from these groups away, we should see their disaffection in the results of the MTF survey question asking respondents if they “want” to serve in the armed forces.

Figure #4 – Likelihood of and Desire for Military Service among Whites

Figure #4 displays responses to the MTF’s likelihood and desire questions among white respondents since 2015. The trend lines between 2015 and 2020 are essentially flat and indicate very little change in white orientations towards military service. Figure #4 also shows, however, a significant drop in white desire (14.8% to 10.0%) occurring between 2020 and 2021.

The drop in desire among whites is broadly consistent with Bryn and Spoehr’s claims but we need to investigate the trends among white Republicans, white Southerners and white rural residents to truly assess their argument. Let’s examine partisanship first. As the data in Figure #5 show, there has been no meaningful decline in desire among white Republicans (indicated, in part, by the fact that the 95% confidence intervals overlap with each other when looking across years). In 2015, for example, 18.1% of white Republicans expressed a desire to serve in the military. In 2021, nearly the exact same share (18.9%) of white Republicans expressed a desire to serve in the military. Despite some minor fluctuations in the exact estimates, there were no statistically significant changes across years in white Republican orientations towards military service. If white Republicans have been repelled from military service by “woke” DEI policies, there is no evidence of it yet.

Figure #5 – Military Attitudes among White Republicans

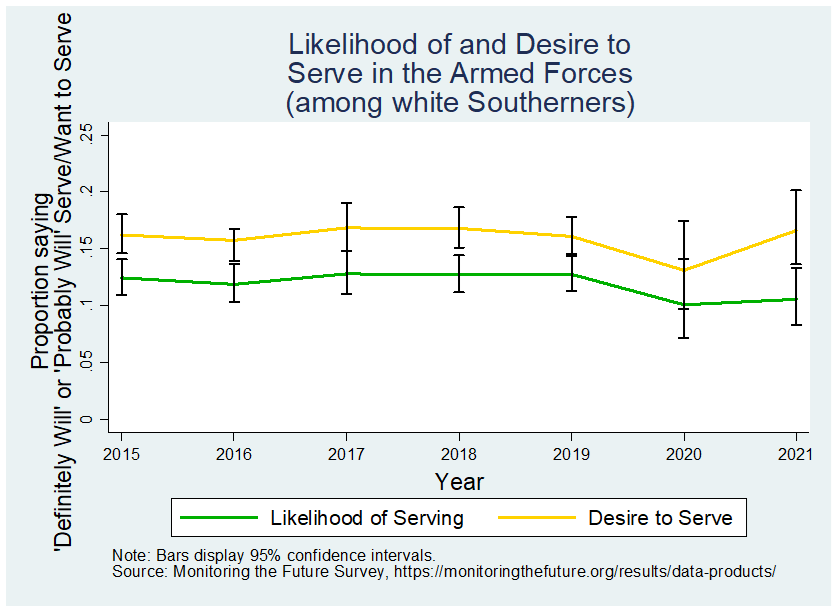

What about the argument that white Southerners are turning away from military service? Once again, there is nothing in the data to indicate that white Southerners have been disincentivized from serving in the armed forces by policies emphasizing “anti-racism,” “gender-sensitivity” or “white privilege.” In 2015, 16.2% of white Southerners wanted to serve in the military. In 2021, 16.6% of white Southerners wanted to serve in the military. Contrary to the claims of Byrn and Spoehr, in other words, there has not been a meaningful decline in desire for military service among white Southerners.

Figure #6 – Military Attitudes among White Southerners

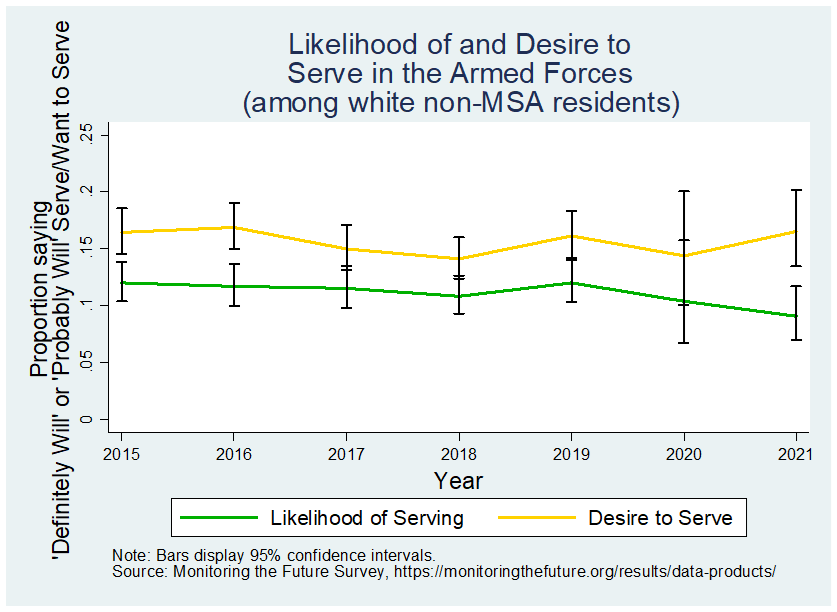

Finally, there’s Byrn and Spoehr’s suggestion that woke DEI policies are delivering an “anti-recruitment” message for rural whites (regardless of which region they hail from). While there is no good measure of urbanicity in the MTF data, the project does provide a dichotomous measure of whether each respondent lives in a large metropolitan statistical area (MSA) or not. In 2015, 16.5% of whites living outside of large MSA’s wanted to serve in the military. In 2021, 16.6% of these whites did. Put differently, there’s really nothing in the MTF data pointing to a change in how rural whites view a career in the armed forces.

Figure #7 – Military Attitudes among White Non-MSA Residents

Collectively, these graphs provide initial evidence against the idea that “woke” DEI policies have significantly depressed white Republican, white Southerner and white rural resident interest in military service. I want to be clear, however, that these results do not mean that Byrn and Spoehr are necessarily wrong about the effects of “woke” DEI policies. It simply means that they are not right yet.

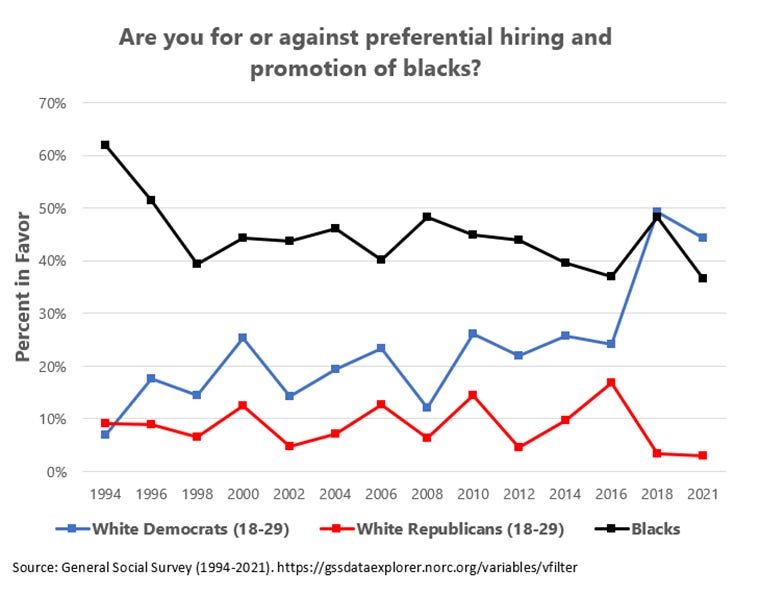

Young white Republicans strongly oppose the kinds of policies Byrn and Spoehr describe. Consider opinions on the question of whether there should be “preferential hiring and promotion of blacks.” Less than 5% of young white Republicans now endorse this kind of race-based affirmative action:

Figure #8 – Support for Affirmative Action Policies by Race and Partisanship

To the extent that policies such as these are implemented by the military, we should expect desire to serve in the military to decline among young white Republicans.

In order for “woke” policies to undermine interest in military, however, they first have to be well-known. Prior to 2022, woke DEI policies in the military received almost no sustained media attention. Indeed, Byrn and Spoehr’s articles were worth publishing in the summer of 2022 precisely because they directed attention to a set of issues that were previously ignored.

At this point, I should point out that the barriers to informing a nontrivial number of young white Republican, Southern, and rural voters of the existence of “woke” military policies are considerable. Most Americans pay little attention to politics and are ignorant about even the most basic and long-standing facts about the American political system. In 2022, for example, less than half of Americans could correctly identify all three branches of government and more than a quarter could not name a single right protected by the First Amendment. Similarly, only 57% of voters under the age of 30 could correctly identify which party controlled the House of Representatives in 2020. If the public has not learned about these foundational aspects of American politics, they are incredibly unlikely to learn about the details of the military’s DEI policies.

With that said, more sustained public discussion of “wokeness” in the armed forces might very well lead to the effects that Byrn and Spoehr describe. We just can’t know until we get more recent data.

If Not White Republicans, Southerners, and Rural Residents, then Who?

While the above analysis helps us reject key parts of Byrn and Spoehr’s argument, it still leaves us with a puzzle: if white Republicans, white Southerners, and white rural residents are not expressing less desire to serve, which whites are responsible for the 5-point decline in desire illustrated in Figure #4?

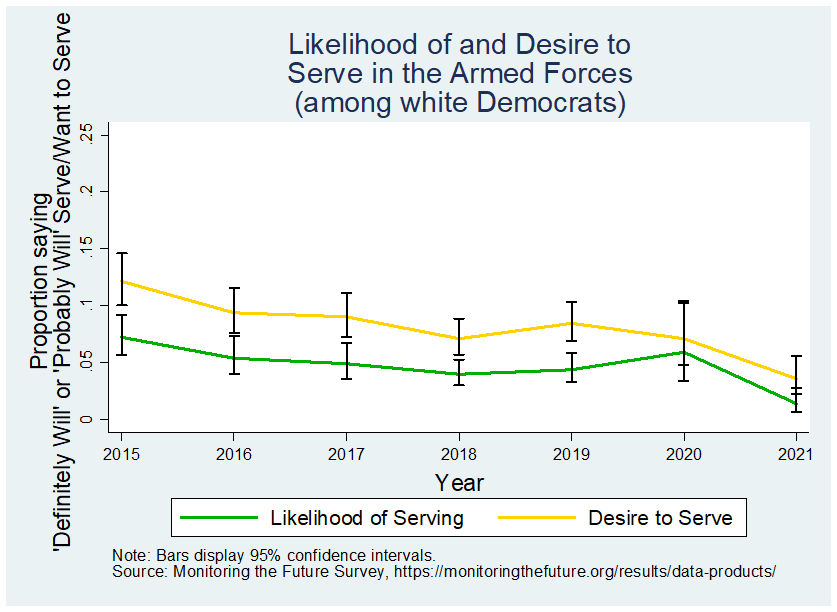

As it turns out, white Democrats –the group most commonly ignored by conservative diagnoses of the recruitment crisis and the group most likely to support the military’s efforts to implement highly progressive DEI policies (see Figure #8) – are actually the ones driving the aggregate decline in white desire discussed above.

Figure #9 – Military Attitudes among White Democrats

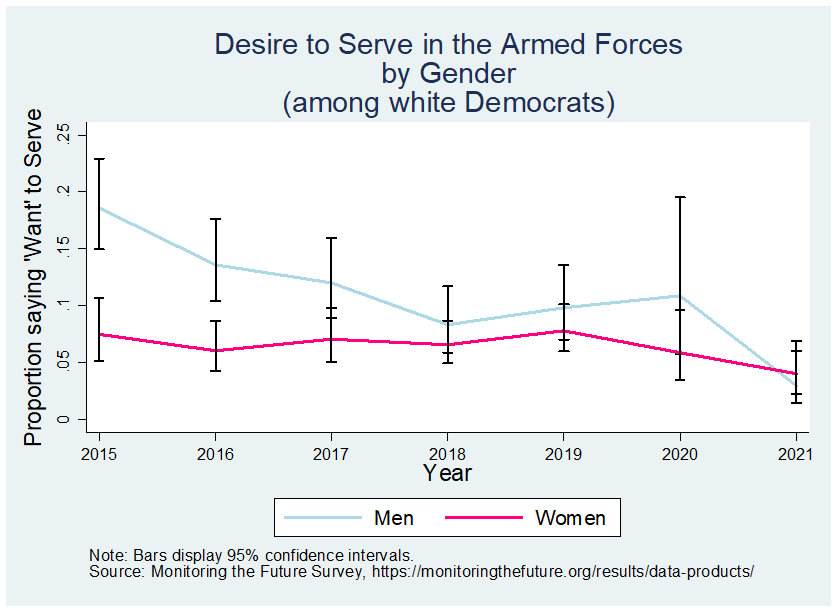

In 2015, 12.2% of white Democrats wanted to serve in the military. That number fell to 3.6% in 2021 (Figure #9). This striking decline does not, however, tell the full story. Most of the collapse in white Democratic interest occurred among men (Figure #10). In 2015, 18.6% of white Democratic men expressed a desire to serve in the military (only slightly lower than the 19.9% of non-Democratic men who wanted to serve). By 2021, that number had dropped to only 2.9%.

Figure #10 – Military Attitudes among White Democrats by Gender

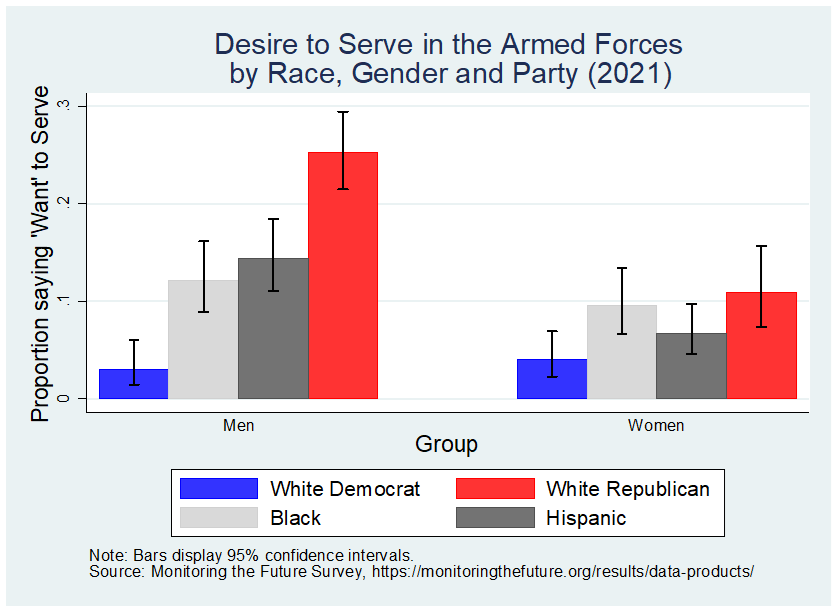

In fact, as Figure #11 shows, black men (12.1%), Hispanic men (14.3%) and white Republican men (25.3%) were all at least 4x more likely than white Democratic men in 2021 to “want” to serve in the armed forces. Democratic white men were also significantly less interested in military service than black women (9.5%) and white Republican women (10.9%).

Figure #11 – Desire to Serve in the Armed Forces by Gender

What’s Dampening Desire among White Democrats?

Why have white Democrats (especially young white Democratic men) soured on military service? Answering this question requires an examination of why people join the military in the first place. Fortunately, understanding the motives that drive young people to enlist in the American military has been a frequent focus of research since the introduction of an all-volunteer force. Survey and in-depth interview data have revealed “a range of motivations for military service, clustering around, on the one hand, the [extrinsic] benefits associated with service [e.g. pay, educational incentives, the opportunity to develop leadership skills, exposure to diverse nations and cultures via travel, an interesting job with variety, and experience to prepare for the future] and, on the other hand, normative commitments to the political community [e.g. patriotism and duty].”

The conservative critique of military “wokeness” alerts us to yet another possibility: orientations towards military service may be shaped by feelings about the military as an institution. It is possible that if young people feel negativelyabout or mistrustful of the military, they will not develop a desire to serve in it (independent of the benefits provided by enlisting and independent of their patriotism). This lack of interest might simply be a function of rational expectations given the perceived nature of the institution. If the military is seen to be untrustworthy, it is unwise to expect it to actually deliver the extrinsic benefits it is promising. If the military is disliked, serving it might not be consonant with one’s sense of patriotism and civic duty.

Overall, then, we want to examine whether perceptions of the military’s extrinsic benefits, the strength of normative commitments to the political community, and feelings towards the military as an institution have disproportionately declined among young white Democrats during the last few years. If so, these changes may be driving the declining desire to serve in the armed forces.

In order to truly assess whether these three attitudes are changing among young white Democrats, we would need to have survey data that: (1) asked questions about economic prospects, patriotism, and feelings towards the military; (2) repeated these questions at multiple points in time between 2015 and 2021; (3) collected sufficiently large sample sizes to yield a nontrivial number of young, white Democrats; and (4) is publicly available.

Unfortunately, there is no polling data that meets all four of these requirements. The best we can do, therefore, is make some educated guesses based on the imperfect data (i.e. meets one or two of the above criteria) that we do have.

Extrinsic Benefits

The extrinsic benefits provided by military service are equal for every group. In order to believe that perceptions about extrinsic benefits are dampening enthusiasm for military service among young White Democratic men, there would have to be a reason why young white Democratic men were the only subgroup among the general population of young white people to change their perceptions of the military’s extrinsic benefits after 2015 (and particularly after 2020).

One’s perception of the military’s extrinsic benefits is likely shaped, in part, by one’s social position. Young people from more affluent backgrounds are likely to be less attracted to the pay, health care, retirement, job training, and other benefits provided by military service. If young white Democratic men are more likely to be raised in affluent backgrounds than other whites, they may find the military’s extrinsic benefits less appealing. More importantly, if the socioeconomic profile of young white Democratic men improved significantly since 2015, it may explain their declining desire to serve in the military.

Unfortunately, the MTF provides no data on the socioeconomic status of its respondents. It is not possible, therefore, to directly test the hypothesis that young White Democratic men’s declining desire to serve might be a consequence of their improving social position after 2015. Needless to say, however, the idea that the social position of young, white Democratic men (and no other group) shifted so uniformly and dramatically that it altered their short-term perceptions of economic benefits is implausible. It is far more likely that feelings towards the country and the military have evolved among this group over the last seven years.

Patriotism

As mentioned above, patriotism is an important predictor of military service. A majority of soldiers consistently describe their service as motivated by a deep-seated sense of patriotism and duty. For example, when soldiers in two infantry battalions were asked in 2002 to identify all the reasons that “were important in your decision to join the Army,” two of the most popular options were “serve country” (65.8%) and “patriotism” (54.9%).

Surprisingly, the MTF data contains no questions related to national pride or the strength of young people’s attachment to their national identity. Gallup has asked a question about patriotism (“How proud are you to be an American -- extremely proud, very proud, moderately proud, only a little proud or not at all proud?”) on a nearly yearly basis since 2001. While Gallup occasionally reports how responses to this question have varied over time and across groups, they do not provide access to the full dataset and only provide a limited number of group-specific analyses. As a result, we cannot identify changes among young white Democrats.

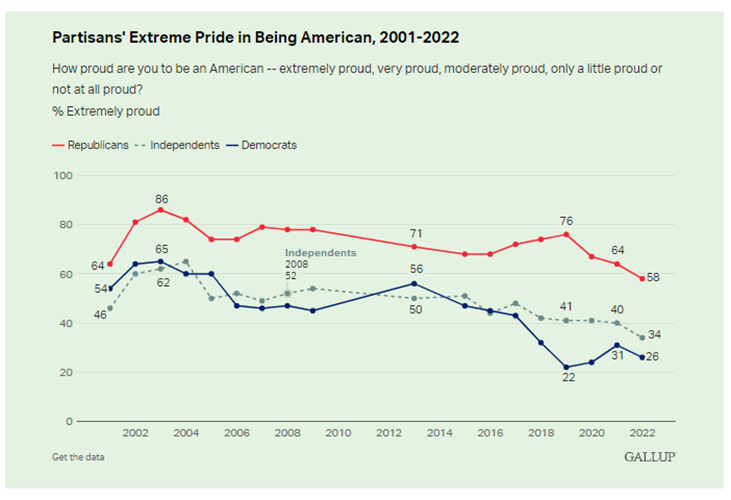

The data that Gallup has made public, however, are consistent with declining levels of patriotism among young White Democrats. As Figure #7 shows, “extreme pride in being American” have fallen more than 20% among Democrats since 2015 and more than 30% since 2013.

Figure #12 – National Pride by Partisanship

The Gallup data also shows that young people generally express far less national pride than older people. Specifically, as Figure #13 demonstrates, only 25% of 18-34 year olds are “extremely” proud to be American (compared to 51% of those 55 and older).

Figure #13 – National Pride by Gender, Age, and Education

Although the publicly available Gallup data cannot definitively prove that young white Democrats have become less patriotic since 2015, the tables and figures they have provided are consistent with this possibility. Indeed, if young Democrats are merely representative of older Democrats and young people more generally, there has likely been a greater than 25% decline in patriotism within the group over the last eight years. Such a decline could easily account for the 10% reduction in desire for military service documented above.

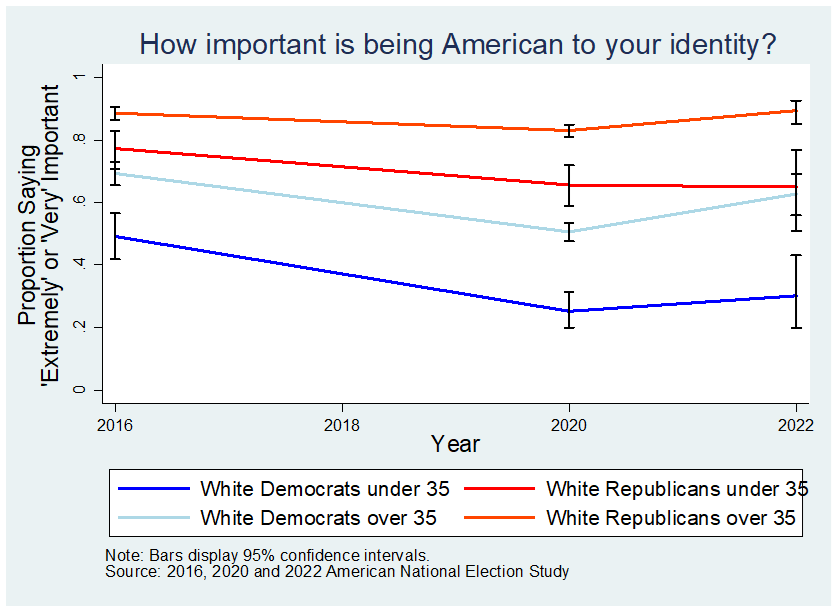

Unfortunately, Gallup is the only survey organization that has asked a question about national “pride” over time. In 2016, 2020, and 2022, the American National Election Study (ANES) asked a slightly different question about national identity: “How important is being American to your identity?” While this question does not directly tap feelings of patriotism or national pride (e.g. respondents may believe that their national identity is important but dislike the country), it does provide a rough proxy for how people feel about their country.

The ANES data contains relatively few young, white Democrats. With this in mind, the ANES shows significant differences across both age and partisanship. As Figure #13 shows, American national identity is losing its salience among young white Democrats. Between 2016 and 2020, the percentage of white Democrats under 35 who claimed that “being American” was “extremely” or “very” important to their identity fell from roughly one-half (49.1%) to one-quarter (25.3%). Young white Democrats are now far less likely than older white Democrats and white Republicans of all ages to say that their national identity is important to them. Once again, this data is consistent with the idea that declining national attachment explains the declining desire to serve in the military among young white Democrats.

Figure #13 – Importance of American Identity by Age and Partisanship

A number of one-off surveys also indicate that young white Democrats may have much lower levels of patriotism than other groups. The Harvard Youth Poll periodically surveys more than 2,000 young Americans (aged 18 to 29). The Youth Poll asks a wide range of questions about politics, current events, and mental health. While the team behind the Youth Poll provides extensive cross-tabs (e.g. data showing variation in attitudes by age, race, gender, and other individual attributes), they do not provide full access to the data. As a result, it is not possible to examine how young, white Democrats respond to the survey’s questions.

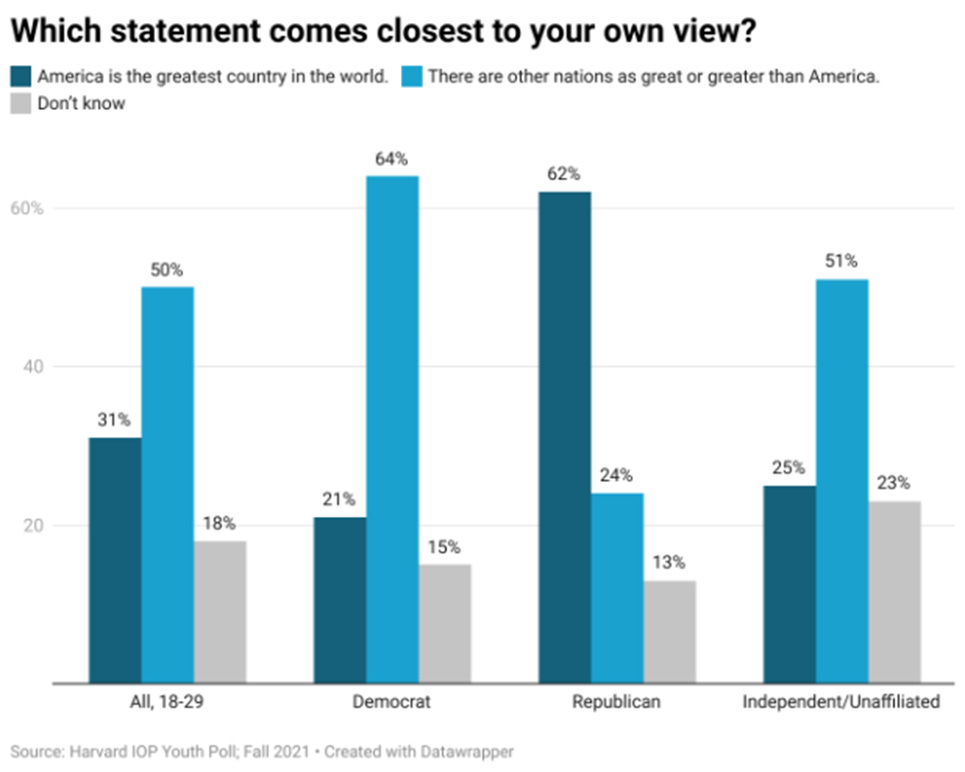

The Fall 2021 iteration of the Youth Poll asked two questions that are helpful in understanding the patriotism of young Americans. First, the poll asked “Which statement comes closest to your own view? ‘America is the greatest country in the world’ or ‘There are other nations as great or greater than America.’” There was a massive partisan gap in responses to this question (see Figure #14). As the survey’s report summarizes, “The views of Democrats and Republicans are inverted with 21% of Democrats saying America is the greatest country and 64% saying other nations are as great or greater; 62% of Republicans believe that America is the greatest with 24% saying other nations are as great or greater.”

Figure #14 – “Great Country” Beliefs among Young People by Partisanship

Additionally, the Harvard Youth Poll asked, “Compared to your parents, do you think you more or less patriotic.” 32% of Democrats reported being “less patriotic” than their parents while only 11% reported being “more patriotic” than their parents. By contrast, 19% of Republicans reported being “less patriotic” than their parents but 21% reported being “more patriotic” than their parents. If young white Democrats are representative of young Democrats overall, the Youth Poll data is indicative of the kind of low and declining patriotism that could explain the collapsing desire of young white Democrats to serve in the armed forces.

More evidence about the declining patriotism of young people can be found in the surveys from the “More in Common Project.” The Project’s 2020 survey discovered that only 51% of Gen Z was proud to be American (compared to 94% of the Silent Generation). What’s more, identifying as “progressive” or “passively liberal” was associated with far less national pride (Figure #15):

Figure #15 – National Pride by Race, Age, Gender, and Ideology

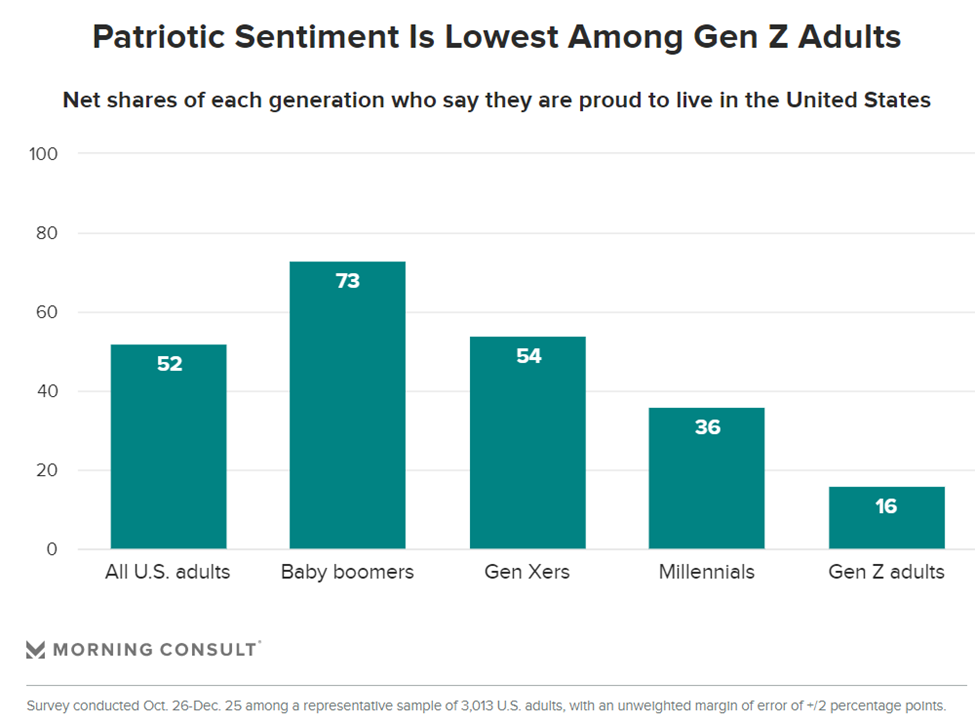

More recently, a Morning Consult poll found that only a tiny percentage of Gen Z feels “proud to live in the United States.”

Figure #16 – Patriotic Sentiment by Age

These disparate surveys tell a common story: patriotism and national pride have evaporated among Democrats and young people over the last decade. Strictly speaking, the evidence summoned here cannot tell us anything about whether young, white Democrats are exceptions to or exemplars of these general trends. The data, however, are entirely consistent with the idea that the attitudes of young, white Democrats are changing in ways that could reduce their interest in military service.

Feelings towards the Military

There is no publicly available, over time data on how young white Democratic men feel about the military as an institution. Gallup has asked a yearly question about confidence in the military but they provide only the topline results (no subgroup analyses) to that question. The Gallup data shows a small and steady overall decline in the public’s confidence in the military since 2015 (dropping from 72% in 2015 to 64% in 2022). It is possible that this decline has occurred entirely among young white Democrats but we cannot know for sure with the data Gallup has provided publicly.

Better data is available from the Reagan National Defense Forum (RNDF). Each year since 2018, the RNDF has asked a nationally representative sample how much “trust and confidence” they have in the military. The RNDF provides crosstab summaries of the results (allowing us to examine how young people and Democrats feel about the military).

The RNDF results show a massive decline in “trust and confidence” among young people (18-29) and Democrats between 2018 and 2021. In 2018, 87% of young people and 92% of Democrats expressed “a great deal” or “some” confidence in the military. In 2021, however, only 67% of young people and 76% of Democrats expressed this sentiment. These results are broadly consistent with the possibility that young white Democratic men have expressed less desire to serve in the armed forces since 2015 as a result of more negative feelings towards the military.

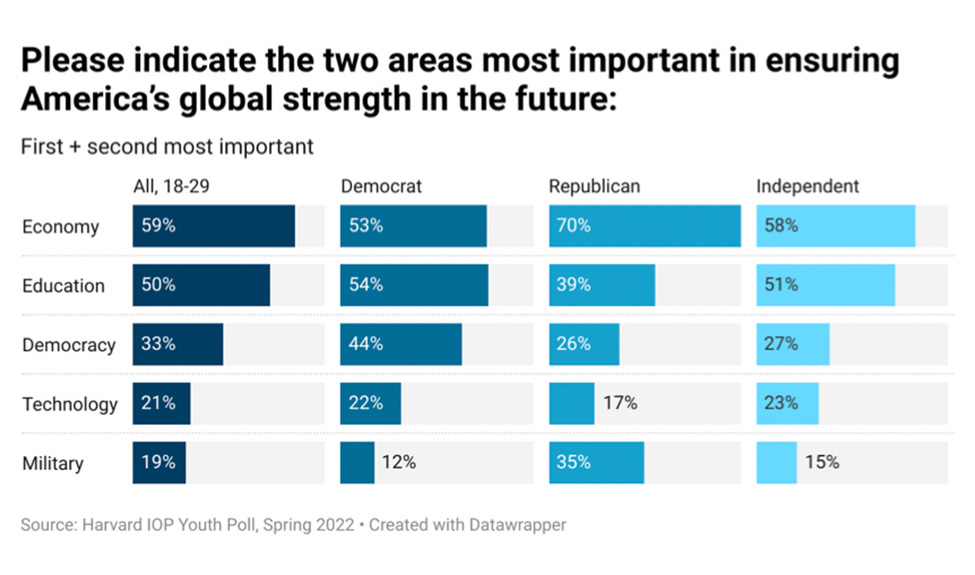

In addition to the Reagan National Defense Forum data, there are a number of polls that provide a snapshot of how the public feels about various aspects of the. Generally speaking, these polls are also consistent with the idea that young white Democrats have disproportionately negative views towards the military. The Spring 2022 iteration of the Harvard Youth Poll, for example, asked young people to identify the most important areas for ensuring America’s global strength in the future. Only 12% of young Democrats identified the military (compared to 35% of young Republicans).

Figure #17 – Perceptions of the Military’s Importance among 18-29 Year Olds by Party

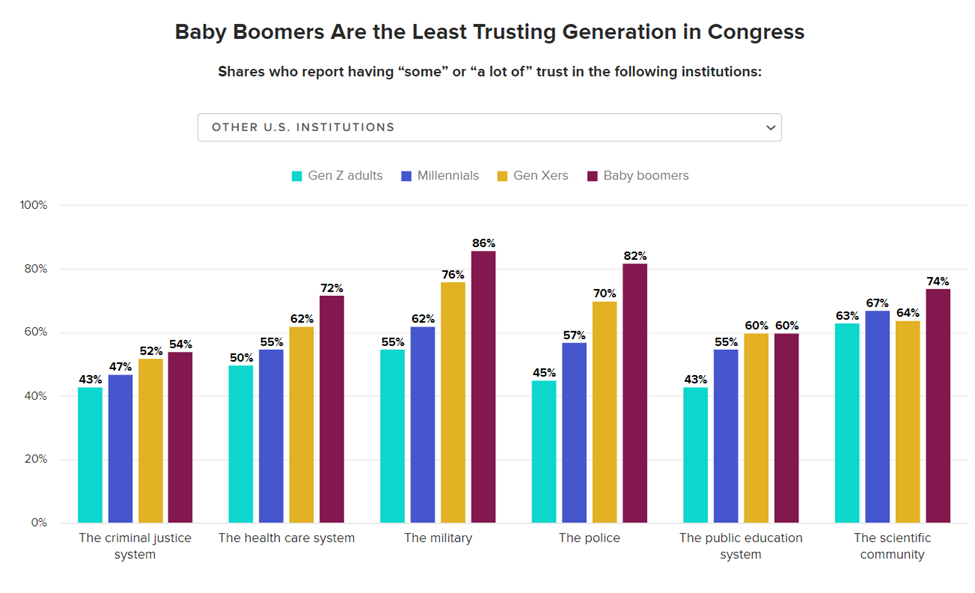

A number of other studies provide data suggesting generational (but not partisan) differences. In one recent survey, for instance, Morning Consult found only 55% of Gen Z (compared to 86% of Boomers) reported feeling “some” or “a lot” trust in the military (Figure #18). In a different Morning Consult survey, 20% of Gen Z said they would stop “buying from a brand they currently shop at if the company supported the US military” (compared to only 8% of Boomers).

Figure #18 – Institutional Trust by Age

Recent data from the Pew Research Center finds similarly negative views towards the military among young people, with only 49% of 18-29 year olds saying that the military has a “positive effect” on the “way things are going in the country these days.”

Figure #19 – Views on the Effects of Institutions by Age

Once again, if white Democrats are merely representative of Gen Z in general, these surveys provide evidence that young white Democrats harbor very negative feelings towards the military. These feelings may be responsible for the fact that young white Democrats are showing little interest in military service since 2015.

The “Great Awokening”

The dramatic and relatively recent attitudinal shifts among young, white Democrats documented here should not be surprising to anyone who has followed American politics over the last eight years. As Zach Goldberg described in an influential 2019 article, white liberals experienced an unprecedented and profound “Great Awokening” sometime between 2012 and 2016:

“The rapidly changing political ideology of white liberals is remaking American politics….This is evident across a range of issues: the rapid growth in white liberals who favor affirmative action for blacks in the labor force; in the increase in white liberals who feel that we spend too little on helping blacks, and that the government should afford them special treatment; in the increase in white Democrats who think it’s the government’s job to ensure “equal income across all races”; and in the increase in white liberals and Democrats who think that white people have ‘too much’ political influence….[and] “recently they became the only demographic group in America to display a pro-outgroup bias—meaning that among all the different groups surveyed white liberals were the only one that expressed a preference for other racial and ethnic communities above their own.”

Goldberg was not alone in recognizing these changes. In a widely read 2019 article for Vox, Matthew Yglesias wrote:

“In the past five years, white liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter. This change amounts to a “Great Awokening” — comparable in some ways to the enormous religious foment in the white North in the years before the American Civil War.”

While Goldberg and Yglesias’ analyses focused mostly on the changing racial consciousness of white liberals, the seismic attitudinal shifts described in their articles have had implications that go far beyond race. As this post has shown, in addition to becoming far more progressive on questions of race, gender, and immigration, young white Democrats have also become far less patriotic and supportive of the American military. A predictable consequence of these increasingly negative attitudes is a growing disinterest in military service. The interrelated set of highly progressive political beliefs, best characterized as “wokeness,” in other words, is beginning to represent an existential threat to the continuation of America’s all-volunteer armed forces.

Conclusion

The American military is facing a recruitment crisis driven, in part, by young people’s declining desire to serve in the military. According to some observers, the Pentagon’s recent moves to implement “woke” DEI policies are alienating young white Republicans from the military. This post has shown, however, there is no evidence to suggest that anything the Department of Defense has done since 2015 is exerting a negative effect on young white Republican desire to serve in the armed forces. This may change in time, of course. Growing wokeness within the military has already precipitated growing attention. Growing attention has the potential to precipitate declining desire among young white Republicans. Yet, as of 2021, there’s nothing to suggest young white Republicans are the source of the military’s recruitment problems.

There’s much to suggest, however, that young white Democrats are an important part of the military’s struggles. While the publicly available data is insufficient for providing definitive proof, there is a mountain of survey evidence consistent with the idea that diminishing enthusiasm for military service among young white Democratic men is a function of their increasingly negative views towards the country and the military.

The military needs to take the “Great Awokening” of young white Democrats seriously and not assume that better pay and more generous benefits will persuade an increasingly reluctant and oppositional demographic group to enlist. “Wokeness” is killing desire to serve in the military and the death of desire might mean the death of an all-volunteer armed forces.

One final note, the evidence presented here about recruitment does not mean that there are no reasons to oppose “woke” military policies. Even if “woke” policies do not act as a form of “antirecruitment,” they still may have serious, negative consequences for the ability of the military to carry out its responsibilities. “Woke” policies may, for example, alienate active duty service members and hurt retention efforts. They may also seriously undermine military readiness. If so, the argument against “wokeness” in the military should be more narrowly framed around these claims and not connected to the ongoing recruitment crisis.

Thanks for the excellent breakdown of data on the topic!

There’s only one factor I can think of that you didn’t address, and that’s personnel retention. I think you’re right that the people most likely to join the military (conservative, rural white males) aren’t very aware of various “woke” policies and practices being implemented and so aren’t dissuaded, but that changes drastically when they actually join. A patriotic young man who shows up for basic training expecting an intensely masculine training environment only to be met with scolding lectures on “white privilege”, “toxic masculinity” and pronoun policing may be fall less likely to stick around beyond the minimum commitment, especially if it becomes clear that promotions are also being manipulated by DEI policies.

This problem compounds with experience, as individuals who have been in for 10+ years (NCOs, Field-Grade officers) have to decide whether to do a full 20 year career or cut their losses early. If they do leave, even in small absolute numbers, it takes many years and a much larger pool of young recruits to replace them and leads to an even more dire recruitment situation. Anecdotally, this could be a growing problem and would seem to be underway as a result of the disgraceful handling of Afghanistan, DEI ideology, and overbearing COVID policies combined.

A tremendously insightful article. The idea that beliefs, and how they manifest, impact recruitment is helpful, but on a more basic level, I think the military career is fundamentally at odds with many of the younger generations preferences (work life balance, family, pay-Pew Studies & Moskos (1977) institutional vs occupational models and his work “The Professional Soldier”).

The class distinction (wealth / education) comes to mind in the early draft era policies that largely targeted those who were of lower class wealth and education. I wonder if what we are seeing is another manifestation (thinking economic class and voting patterns = https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/11/09/biden-voting-counties-equal-70-of-americas-economy-what-does-this-mean-for-the-nations-political-economic-divide/)

I find this topic very fascinating as it is a manifestation of America and includes both American government and international relations considerations.

Thanks for writing / sharing.